Difference Between General and Limited Partners: Roles, Liabilities, and Returns

Difference Between General and Limited Partners: Roles, Liabilities, and Returns

Learn the difference between general and limited partners, including roles, liability, and potential returns to guide your real estate investments.

Domingo Valadez

Jan 2, 2026

Blog

At its core, the difference between a general partner and a limited partner boils down to a simple trade-off: control versus capital.

A General Partner (GP) is the hands-on manager—the one steering the ship. They're in charge of running the business, calling the shots, and in return, they shoulder unlimited personal liability for its debts. On the flip side, a Limited Partner (LP) is a passive investor. Their job is to provide the fuel (capital) for the journey, and in exchange, they get a slice of the profits without having any management duties. Crucially, their financial risk is capped at the amount they invested.

Defining the Roles of General and Limited Partners

If you’re stepping into the world of partnership investments like real estate syndications or private equity, getting a firm grip on the GP vs. LP distinction is non-negotiable. They might both be called "partners," but their roles, responsibilities, and the risks they face are on completely different planets. This division of labor is the bedrock of the entire investment structure, dictating everything from daily operations to how the money gets split.

Think of the GP as the operator, the one with the boots on the ground and the expertise to make the business plan a reality. They handle it all—finding the deal, running the numbers, managing the asset, and keeping investors in the loop. This deep involvement gives them total control over the partnership's strategy and execution. You can see this in action with prominent venture capital firms, which actively manage funds and make critical investment decisions for their LPs.

The LP, meanwhile, plays a purely financial part. They contribute the equity needed to get the project off the ground, placing their trust in the GP's ability to turn their capital into a healthy return. They are the classic "silent partners," enjoying the financial upside without the headaches of day-to-day management. It's a structure that opens doors for people to invest in deals they otherwise wouldn't have the time or specialized knowledge to handle themselves.

The GP is the pilot of the airplane, responsible for navigation, operations, and the ultimate safety of the flight. The LPs are the passengers in first class; they've paid for a seat to the destination but are not expected to fly the plane.

This entire arrangement is cemented in a legal framework designed to protect the passive status of the LP while giving the GP the authority to act decisively. The table below breaks down these two critical roles for a quick side-by-side view.

Quick Comparison of General Partner vs Limited Partner

This table provides a summary of the primary distinctions between General and Limited Partners in a real estate syndication.

In short, the partnership relies on both roles to succeed. One brings the vision and execution, the other brings the capital to make it all possible.

A Detailed Comparison of GP and LP Responsibilities

When you get down to brass tacks, the real difference between a general partner and a limited partner shows up in their day-to-day work, their legal standing, and ultimately, how they make money. The entire partnership model is built on a clear, legally defined separation of these roles. Getting these distinctions right is non-negotiable for anyone in private investments, whether you're the one running the deal or the one funding it.

Let's break down the key areas that define the GP and LP roles, from who calls the shots to who's on the hook if things go south.

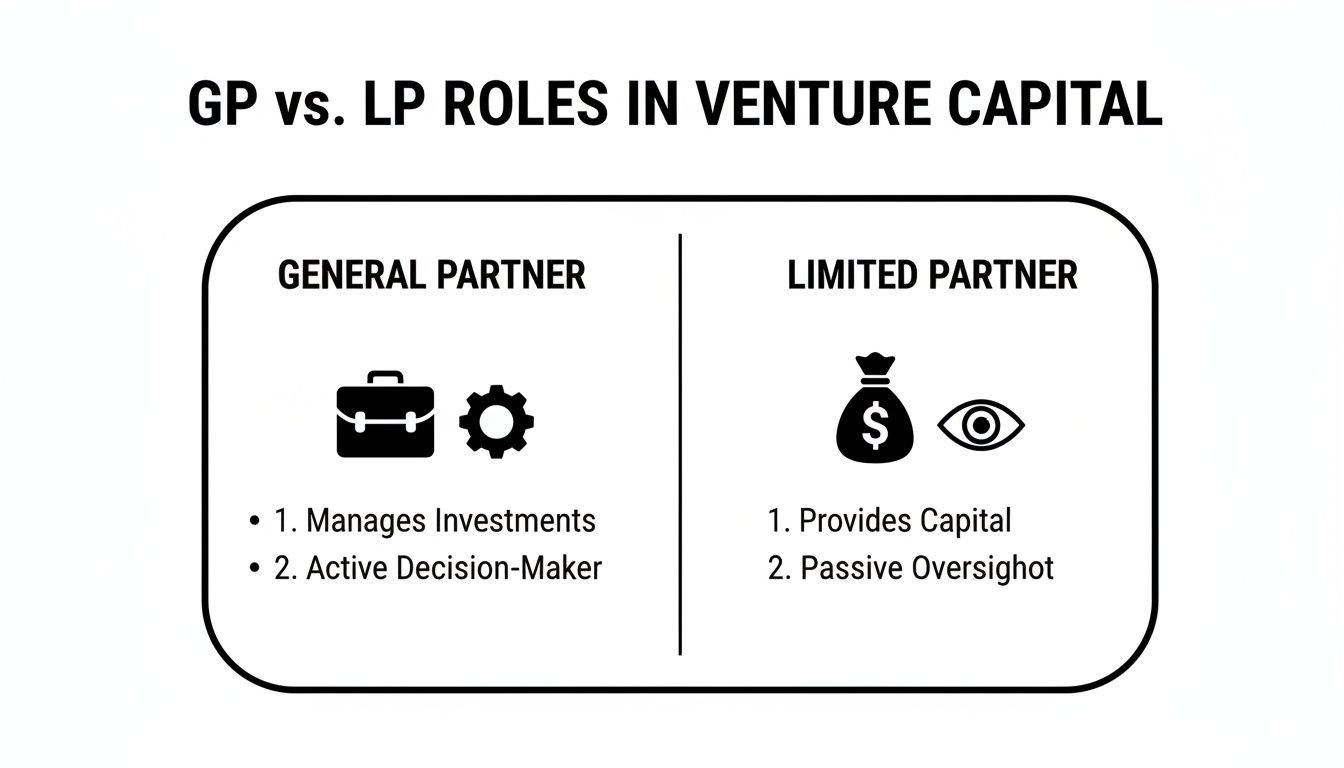

This infographic gives a great high-level view of how the operational and financial roles of General Partners and Limited Partners stack up against each other.

As you can see, the GP is the engine driving the whole operation forward. The LP, on the other hand, provides the fuel from a much safer, hands-off position.

Management and Operational Control

The most glaring difference is who's in charge. The General Partner has total, unquestioned authority over the partnership's strategy and daily grind. They run the show.

It's the GP's job to:

* Execute the business plan: In real estate, this means managing the property and overseeing renovations. In venture capital, it’s about mentoring portfolio companies.

* Make the tough financial calls: The GP lines up the financing, manages the budget, and decides the perfect time to sell.

* Handle all the paperwork: This covers everything from legal compliance and accounting to keeping investors in the loop.

Meanwhile, Limited Partners have exactly zero management control. Their role is designed to be passive, and for good reason—getting too involved can actually strip away their liability protection. LPs put up the cash and trust the GP's expertise to turn it into a profit.

Liability and Personal Risk Exposure

This is arguably the most critical distinction from a legal standpoint. A General Partner faces unlimited personal liability. If the partnership gets sued or can't pay its bills, creditors can come after the GP's personal assets. We're talking about their house, their car, their savings—everything is on the table.

Limited Partners, thankfully, have limited liability. Their financial risk is capped at the exact amount of money they invested. If a deal goes belly-up, an LP can lose their entire investment, but that's where the bleeding stops. Their personal wealth is safely walled off from the partnership's creditors.

This liability shield is the core reason LPs get involved in the first place. It gives them a ticket to high-return opportunities without betting the farm.

While that liability shield is strong, it's not invincible. It’s worth understanding the concept of piercing the corporate veil, which describes rare situations where a court might hold LPs accountable, usually in cases of fraud or a blatant disregard for corporate formalities.

Fiduciary Duties and Legal Obligations

Both partners have legal duties, but they are far from equal. The GP owes a strict fiduciary duty to the LPs, which is the highest standard of care recognized by law. This legally binds the GP to always act in the best interests of the partnership and its investors.

This duty breaks down into two main components:

1. Duty of Care: The GP has to manage the fund’s affairs competently and diligently. No slacking.

2. Duty of Loyalty: The GP must put the partnership first, steering clear of conflicts of interest or any self-serving deals.

Limited Partners don't carry this same heavy burden. Their main obligation is straightforward: contribute the capital they promised in the agreement. They aren’t expected to act on behalf of the fund or the other partners.

Capital Contributions and Compensation

The financial arrangement is a direct reflection of these different roles. LPs typically provide the lion's share of the investment equity, often 90-95% of the total capital required for a deal.

The GP, also known as the sponsor, usually puts in a smaller amount, maybe 5-10%, to have some "skin in the game." This ensures their financial interests are aligned with the LPs.

The way each partner gets paid reflects this division of labor and capital:

* General Partners earn money through a series of fees (for acquiring an asset, managing it, and eventually selling it). Their biggest reward, however, comes from a disproportionate share of the profits, known as carried interest or the "promote." It's their bonus for a job well done.

* Limited Partners receive their proportional share of the profits based on how much they invested. Their returns come after all the GP's fees and the promote have been paid out, as spelled out in the waterfall distribution schedule.

Navigating the Legal and Documentary Framework

The relationship between a General Partner (GP) and a Limited Partner (LP) isn't built on a handshake—it's forged in meticulously crafted legal documents. These agreements are the absolute foundation of any partnership, defining everything from profit splits and management fees to the specific duties of each party.

For a GP running the deal or an LP putting up capital, getting a firm handle on these documents is non-negotiable. They are what turn abstract roles into concrete, legally enforceable obligations, making sure everyone is on the same page from the get-go. Without them, you’re just inviting financial and legal chaos.

The Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA)

At the very core of any real estate syndication sits the Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA). This is the master contract that governs the entire partnership, spelling out the rights, responsibilities, and limitations for both the GP and every LP involved. Think of it as the constitution for the investment.

An LPA is almost always a long, dense document drawn up by securities attorneys, but its purpose is simple: to create a clear rulebook for how the entire deal will operate. For any investor, reading this document isn't just a suggestion; it's an absolute must.

The LPA is the single source of truth for the partnership. It dictates the terms of engagement and provides the mechanisms to resolve disputes, protecting both the GP's operational authority and the LP's financial interests.

While every LPA is customized for a specific deal, they all share a few key sections that draw the bright line between a general and a limited partner. Really understanding what is a limited partnership agreement is the first critical step to becoming a savvy investor.

Here are a few of the non-negotiable elements you'll find in an LPA:

- Roles and Responsibilities: It explicitly states that the GP manages the asset while LPs are strictly passive investors with zero say in day-to-day operations.

- Capital Contributions: The agreement specifies exactly how much capital each LP is committing and lays out the process for capital calls if more funds are ever needed.

- Distributions and Waterfall: This is the big one. It details how and when profits are paid out, including any preferred returns for LPs and the GP's carried interest (promote).

- Fees: It provides a transparent breakdown of every fee the GP can earn, such as acquisition, asset management, and disposition fees.

- Reporting Requirements: The LPA sets clear expectations for communication, defining the frequency and type of financial reports and updates the GP must send to LPs.

This document is what legally cements the LP’s passive role and the GP’s active, fiduciary-bound position.

The Subscription Agreement

If the LPA is the rulebook for the whole team, the Subscription Agreement is the contract an individual LP signs to officially join. It’s essentially your application to get into the game. By signing it, an investor subscribes to purchase a certain number of shares or units in the partnership.

This document doesn't stand alone; it works hand-in-glove with the LPA. Signing the subscription agreement is the LP's formal way of saying, "I've read the LPA, I agree to its terms, and I'm in."

The Subscription Agreement serves a few crucial purposes:

- Formalizes the Investment: The LP commits to a specific dollar amount.

- Confirms Investor Status: The investor must certify their standing, usually as an "accredited investor," which is a legal requirement for most private deals.

- Acknowledges Risk: The LP formally confirms they've reviewed all the offering documents (especially the LPA) and fully understand the risks involved.

Together, the LPA and the Subscription Agreement create a solid legal structure. They draw clear lines in the sand for the GP-LP relationship, protecting everyone involved and setting the stage for a transparent, well-run investment.

How Taxes Differ for GPs and LPs

When tax season rolls around, the lines between a general partner and a limited partner become incredibly sharp. The way returns are taxed isn't just a minor detail; it’s a core difference that directly shapes the net profit each partner ultimately keeps.

The key to understanding this is pass-through taxation. Partnerships don’t pay their own income taxes. Instead, all profits and losses are “passed through” to the partners, who report everything on their personal tax returns. Each partner gets a Schedule K-1 that details their share of the partnership’s income, credits, and deductions, neatly avoiding the double taxation you see with C-corporations.

The General Partner’s Tax Reality

For a General Partner (GP), any income they earn from managing the partnership—like management fees or their share of the profits—is almost always considered active, ordinary income. The IRS sees the GP as actively engaged in a business.

This means their earnings are subject to regular income tax rates plus self-employment taxes for Social Security and Medicare. That self-employment tax adds a hefty 15.3% to a significant portion of their income. It’s the trade-off for having boots-on-the-ground control and a larger slice of the profits.

A GP's compensation is essentially treated like salary from a business they actively run. The tax burden reflects their hands-on involvement and management responsibilities.

The Limited Partner's Tax Advantage

Limited Partners (LPs), on the other hand, see their returns treated as passive income. Because they aren't involved in the day-to-day work, their profits are not subject to self-employment taxes. This is a massive tax benefit and a primary draw for passive investors.

In real estate, the perks for LPs get even better. Here's how that passive structure plays out:

- Depreciation Benefits: Real estate investors can claim depreciation, a non-cash expense that reduces taxable income. This "paper loss" can flow through to the LP via their K-1, potentially sheltering their cash flow from taxes, even if the property is profitable.

- Offsetting Passive Gains: Any passive losses generated from the investment (like from depreciation) can be used to offset passive income from that same deal or other passive investments in their portfolio.

This favorable tax treatment cements the LP's role as a true capital provider. Their returns are taxed less because they aren't earned through active labor, creating a clear and financially meaningful distinction from the GP.

Exploring Modern Dynamics in GP and LP Relationships

The old, rigid lines between a General Partner (GP) and a Limited Partner (LP) are starting to blur. While the core difference still boils down to active management versus passive capital, the relationship itself is becoming far more dynamic. Today’s market pressures and savvier investors are stretching the limits of this traditional structure.

LPs are no longer satisfied writing a check and disappearing for ten years. They’re looking for more influence, lower fees, and a more direct hand in the deals they fund. This has pushed GPs to get creative, designing partnership structures that offer greater transparency and alignment to meet this growing demand.

The Rise of Co-Investment Opportunities

One of the biggest changes we're seeing is the explosion of co-investment opportunities. This lets LPs invest directly into a specific deal right alongside the main fund. Instead of just committing to a blind pool, an LP can write a separate, often much larger, check for an asset they really believe in.

For a Limited Partner, this hybrid approach is a game-changer:

* Greater Control: They get to pick and choose which assets to double down on, giving them a more active role in shaping their portfolio.

* Reduced Fees: Co-investments often carry much lower management fees and carried interest—sometimes even on a “no fee, no carry” basis—which can seriously juice their net returns.

* Deeper Due Diligence: It’s a fantastic opportunity for an LP to get an inside look at the GP’s deal flow and underwriting process.

From the GP's perspective, offering co-investments is a smart way to strengthen relationships with their most important LPs. It also helps them raise the extra capital needed for a big acquisition without having to dilute the returns for everyone else in the main fund.

The Surge in GP-Led Secondary Transactions

Another trend that’s completely reshaping the landscape is the boom in GP-led secondary transactions. The old secondary market was all about LPs trading their fund stakes with each other. The modern GP-led version flips that script: the GP initiates the sale of one or more assets from an older fund into a new "continuation vehicle" that they also manage.

This move gives GPs a way to offer liquidity to LPs who want to cash out, all while holding onto their best-performing assets. New LPs come in to fund the new vehicle, giving the GP fresh capital and a longer runway to maximize the asset's value.

A GP-led secondary is a strategic tool that aligns interests by offering a liquidity option for early investors while allowing the sponsor to continue executing a successful business plan for a prized asset.

This isn't just a niche strategy anymore; it's a dominant force. Recent 2024 data shows that GP-led deals accounted for a staggering 65% of total real estate secondaries market activity, valued at $15.8 billion. It’s the fastest-growing part of the market, fueled by the need for liquidity and investors' desire for targeted exposure to proven assets. You can learn more about the growth of the real estate secondaries market and what it means for partnerships.

These shifts prove that the once-clear separation between GPs and LPs is fading. As investors demand more sophisticated and tailored options, the most successful partnerships will be the ones that embrace flexibility and find new ways to align the interests of active managers and their capital partners.

Best Practices for Managing the GP and LP Relationship

If you're a General Partner, your ability to build and maintain trust with your Limited Partners is everything. It's the absolute bedrock of a successful, long-term business. At its core, the dynamic between a GP and an LP boils down to active management versus passive capital—a relationship that can only thrive on genuine confidence.

Success starts with radical transparency. You need to establish clear, consistent communication from the moment an LP commits. Your investors should never be left wondering about the status of their capital. Proactive, detailed reporting isn't just a nice-to-have; it's a non-negotiable part of your fiduciary duty.

This means sending out regular monthly or quarterly updates on how the asset is performing, what the financials look like, and how you’re tracking against the original business plan. And when problems pop up—which they inevitably will—address them head-on. Communicate the issue promptly and honestly, but always come with a clear plan for how you're going to fix it.

Structuring Deals for Aligned Interests

Beyond just talking a good game, the deal structure itself needs to scream alignment. Nothing does this better than a significant GP co-investment. When LPs see you have a meaningful amount of your own skin in the game, it proves you’re focused on the outcome, not just collecting fees.

The other piece of this puzzle is the return structure. Setting up the waterfall with a fair preferred return is critical. It ensures LPs get paid first, which is exactly what they signed up for. This shows that your big payday—that carried interest or "promote"—is directly tied to your ability to deliver solid returns for the people who trusted you with their money.

The strongest GP-LP relationships are built on a simple premise: we win together. An aligned structure ensures the GP is incentivized to protect LP capital and maximize returns, not just to collect fees.

Leveraging Technology to Build Confidence

In a crowded market, one of the best ways a sponsor can stand out is by delivering a seamless, professional investor experience. The right technology can be a game-changer here, streamlining your back-office operations so you can focus on what really matters: managing the asset.

Here are a few practical ways to do it:

* Automate Distributions: Use ACH to make sure payments are on time and error-free. It's simple, but it makes a huge difference.

* Provide a Secure Portal: Give investors a single, professional online hub where they can easily find all their documents—legal agreements, financial reports, and tax forms like the Schedule K-1.

* Simplify Fundraising: Use modern software to handle subscription documents and investor accreditation. It makes the whole process smoother and more efficient for everyone involved.

Ultimately, when you manage the relationship well, LPs feel less like a line item on a cap table and more like genuine partners. This approach is how you turn a one-off deal into a lasting relationship, building a reliable capital base you can count on for years to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

When you're dealing with real capital, the specifics of partnership structures matter. A lot. Getting the difference between a general and limited partner right is fundamental to understanding your risk, responsibilities, and potential upside. Let's tackle a few common questions that come up for both sponsors and investors.

Can a Limited Partner Become a General Partner?

Yes, but it's not a simple switch. An LP can transition to a GP, but it’s a major legal and structural event that requires a formal amendment to the Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA), which all the other partners have to agree on.

The second an LP starts acting like a manager, they lose their liability protection. They’re no longer just risking their initial investment; their entire net worth is on the line, just like any other GP.

This isn't just a change in title. It's a total shift in your legal and financial reality. You trade the safety of limited liability—the main reason for being an LP—for a seat at the operating table.

Can an Entity Be a General Partner?

Not only can it, but it absolutely should be. It’s standard practice for the GP to be a Limited Liability Company (LLC) or a corporation instead of a person. This is all about creating a crucial layer of protection.

By setting up an LLC to act as the GP, the unlimited liability is contained within that business entity. This structure shields the personal assets of the sponsors—the people actually running the show—from the partnership's debts and legal troubles. If you skip this step, your personal wealth is completely exposed.

What Happens if a Limited Partner Gets Too Involved?

To keep their liability shield, a limited partner has to stay passive. If an LP starts meddling in the day-to-day management or making operational calls, they risk being legally reclassified as a general partner by the courts.

This can happen if they start:

* Making hiring and firing decisions.

* Negotiating contracts for the partnership.

* Exercising significant control over the partnership’s bank accounts.

If a court sees this behavior, it might "pierce the corporate veil," which strips away their limited liability protection. Suddenly, they're on the hook for all the partnership's debts, just like a GP. For any LP, the line between passive investor and active manager is one you don't want to cross.

Ready to streamline your next real estate deal? Homebase provides an all-in-one platform for managing fundraising, investor relations, and distributions, so you can focus on what matters most—closing deals and maximizing returns. Learn more about how Homebase can simplify your syndication process.

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

DOMINGO VALADEZ is the co-founder at Homebase and a former product strategy manager at Google.

What To Read Next

A Guide to Real Estate Financial Modelling for Syndicators

Blog

Master real estate financial modelling with this guide. Learn to build models that analyze deals, forecast returns, and build unwavering investor confidence.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

© 2026 Homebase. All rights reserved.