A Guide to Being an LP in Private Equity Real Estate

A Guide to Being an LP in Private Equity Real Estate

Discover what it means to be an LP in private equity. This guide explains capital calls, distributions, and the key terms for real estate investors.

Domingo Valadez

Feb 20, 2026

Blog

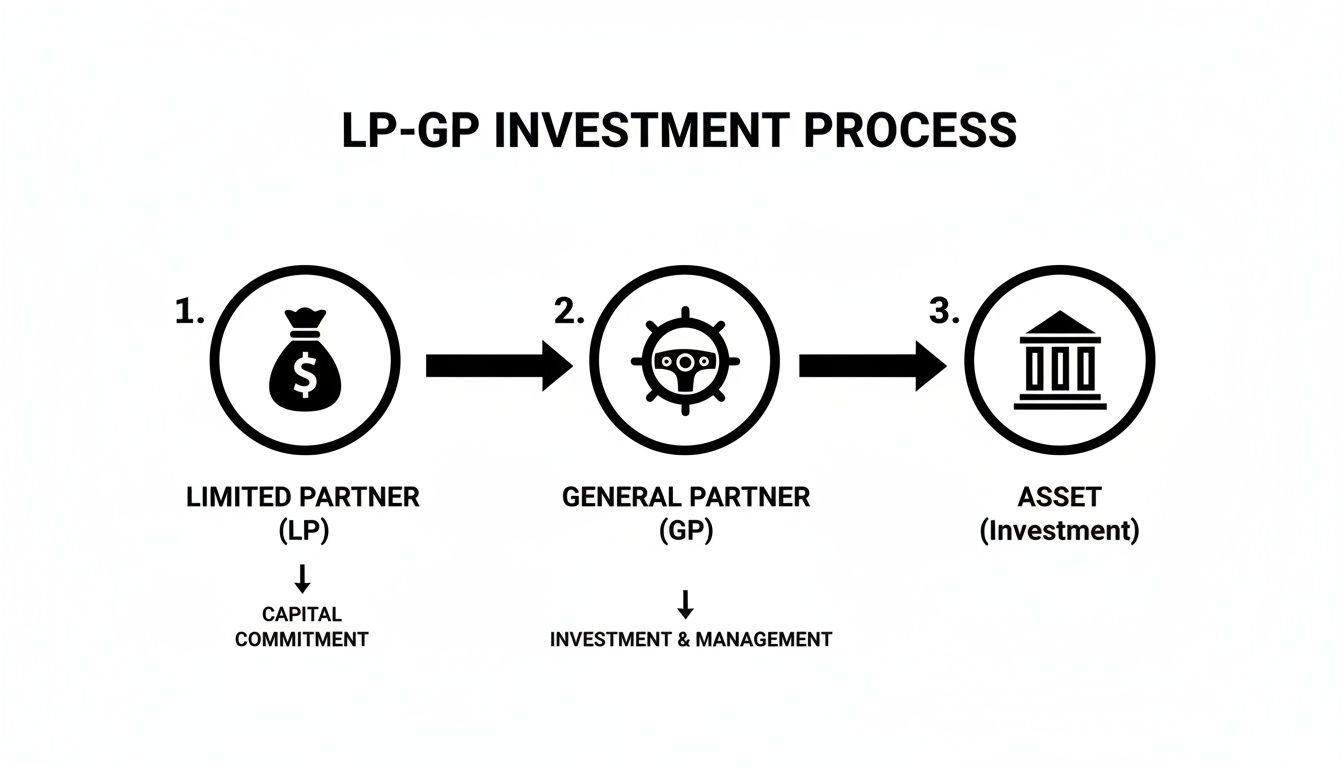

So, what exactly is an LP in private equity? The term stands for Limited Partner, and it refers to a passive investor who puts up the capital for a fund. They aren't involved in the day-to-day grind of managing the investments.

Think of them as the financial backers. The General Partner (GP), on the other hand, is the one in the driver's seat, actively managing the assets and calling the shots. This dynamic is the engine that powers the entire private equity real estate world.

Understanding the Role of an LP in Private Equity

Let's use an analogy. Picture a real estate syndication as a high-performance race car. The General Partner (GP) is the skilled driver—the expert navigating the twists and turns of the market and making split-second strategic decisions. The Limited Partners (LPs)? They provide the high-octane fuel—the capital—that gets the car on the track and across the finish line.

It's a two-way street. Without the LPs, the GP has a brilliant race strategy but an empty gas tank. And without the GP, the LPs have a pile of capital but lack the specialized know-how, connections, and time required to find, buy, and manage a massive apartment complex or office building. This symbiotic relationship is the absolute foundation of private equity.

The Core Dynamic: Capital vs. Operations

At its heart, the difference between a GP and an LP boils down to active management versus passive investment. An LP's main job is simple: provide the committed capital when the GP "calls" for it. For taking that risk, they get a slice of the profits without ever having to deal with tenant issues, property maintenance, or any other operational headache.

This setup gives investors some powerful advantages:

- Access to Expertise: LPs tap into a level of professional management and deal flow that would be nearly impossible to find on their own.

- Limited Liability: The "limited" in Limited Partner is key. An LP's financial risk is capped at the amount they invested. They aren't on the hook personally if the fund takes on debt.

- Passive Income Potential: It’s a way for investors to get into large-scale real estate deals and earn returns without quitting their day job.

A big part of this world is the specific investment vehicle used to pool the money. To get a better handle on this, it's worth understanding the private placement meaning, as these private offerings are the common structure for these deals, each with its own opportunities and risks.

The LP-GP partnership is built on a clear trade-off: LPs exchange control for convenience and limited liability, while GPs take on full operational responsibility and higher risk in exchange for a larger share of the profits.

This structure truly is the bedrock of real estate syndication. If you want to dive deeper into the specific duties of each role, you can learn more about https://www.homebasecre.com/posts/general-partners-and-limited-partners in our detailed guide.

How an LP's Capital Commitment Actually Works

When you become a Limited Partner (LP) in a private equity fund, you don't just write one big check on day one. Instead, you make a capital commitment. Think of it less like a lump-sum payment and more like establishing a line of credit for the General Partner (GP) to use. You might pledge $250,000, but that money stays in your bank account until the GP finds a deal worth pursuing.

This structure is incredibly efficient. It prevents a massive pile of cash from sitting idle, earning next to nothing, while the GP scouts for opportunities. The GP "calls" for the capital only when it's time to acquire a property, fund renovations, or cover other direct fund expenses. For you, the LP, your money keeps working for you until the very moment it's needed for the investment.

Capital Calls: The Request for Funds

So, how does the GP get the money? When they've identified a promising asset and have it under contract, they'll issue a capital call. This is a formal request sent to all LPs, asking for a specific portion of their total commitment.

Let's say the GP needs to raise 10% of the total fund to close a new deal. If your commitment is $250,000, you’ll receive a notice asking you to wire $25,000 by a certain date. It's a straightforward process, but it's also a serious obligation. Failing to meet a capital call can have significant consequences, which are always spelled out in the fund's legal documents. The entire deal hinges on every LP fulfilling their pledge.

This flow chart gives a great visual of how LP capital moves to the GP, who then puts it to work in a real-world asset.

It's a perfect illustration of the fundamental partnership: LPs provide the fuel, and the GP drives the investment vehicle.

Distributions and the Waterfall Model

The exciting part comes when the GP generates cash flow from an asset or sells it for a profit. The money flows back to investors through distributions, but it's not a simple even split. Nearly every private equity deal uses a structure called the distribution waterfall to ensure profits are paid out in a fair, prioritized sequence.

Imagine filling a series of buckets, one at a time. The water can't flow into the next bucket until the one before it is completely full.

- Return of Capital: The very first bucket to be filled is yours. LPs get 100% of their contributed capital back before anyone else sees a dime of profit. This is rule number one: make the investors whole.

- Preferred Return: Once your initial investment is returned, the next bucket is the preferred return (often called the "pref"). This is a threshold, typically around 7-8% annually, that LPs must earn before the GP can share in the profits. It's your reward for taking the initial risk.

- GP Catch-Up: After the LPs have received their capital back and their preferred return, the GP gets a chance to "catch up." In this phase, they'll often receive a much larger portion of the profits until their share reaches a pre-agreed-upon level.

- Carried Interest Split: Now that all the preliminary buckets are full, any remaining profit is split. This final split is typically 80/20, with 80% going to the LPs and 20% to the GP. The GP's share of the profit is known as carried interest, or the "promote."

This waterfall model is a cornerstone of private equity because it beautifully aligns everyone's interests. The GP only makes significant money after their investors have been made whole and have earned a solid return first.

The Different Types of LPs in Real Estate Investing

The term "LP" isn't a one-size-fits-all label. It covers a huge range of investors, and each one comes to the table with different goals, checkbook sizes, and ways of making decisions. A General Partner (GP) would never use the same pitch for a small retail shop and a massive corporation; the same logic applies to LPs. Knowing who you're talking to is one of the most critical skills in private equity real estate.

An LP in private equity is not some uniform entity. The ecosystem is a mix of massive institutions managing billions, private family investment firms, and individuals making their first foray into passive investing. If you want to build lasting partnerships, you first have to understand what makes each of them tick.

Institutional Investors

At the very top of the food chain, you'll find the institutional investors. These are the giants of the industry—large-scale players who professionally manage enormous pools of capital on behalf of others.

- Pension Funds: Think of the organizations that manage retirement funds for teachers, firefighters, or state employees. Their primary job is to generate stable, long-term returns to meet future pension payouts. Because of this, their due diligence process is notoriously thorough and can feel painstakingly slow, often involving layers of committees and third-party consultants.

- Endowments: These are the investment arms of universities and large foundations, tasked with growing a capital base to support their missions forever. Much like pension funds, they have incredibly long investment horizons and place a huge premium on protecting their capital while still achieving growth.

- Insurance Companies: When you pay your insurance premium, that money gets invested to ensure the company can cover future claims. Their strategies are often conservative and heavily regulated, with a strong preference for predictable, cash-flowing properties.

For these titans, a single investment can easily be in the tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars. They are the definition of "patient capital," but you don't just walk in and get a check. A GP needs a rock-solid track record and institutional-quality operations to even get a meeting.

Family Offices

Sitting in a really interesting spot between the big institutions and individual investors are family offices. These are essentially private wealth management firms built to serve a single ultra-high-net-worth family (or a small handful of them). A family office is like a personal CFO for the ultra-rich, handling everything from investments and philanthropy to estate planning.

They often have sophisticated in-house investment teams and can write checks that rival smaller institutions. The big difference? They can move fast. Without the bureaucracy of a pension fund committee, a family office can jump on a compelling deal much more quickly. Their motivations can also be more personal, sometimes blending pure financial returns with goals like generational wealth transfer or making a specific community impact.

A key advantage of working with family offices is their ability to blend institutional-sized checks with the speed and flexibility of a private investor. They often seek direct relationships with GPs they trust.

High-Net-Worth Individuals

Finally, we have the broadest and most diverse group of LPs: high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) and accredited investors. These are successful doctors, lawyers, entrepreneurs, and corporate executives investing their own personal capital.

While their individual checks are smaller—typically ranging from $50,000 to a few million—their collective buying power is massive. HNWIs are often drawn to private real estate for portfolio diversification away from the stock market and for its potential tax advantages. They really value a direct line of communication with the GP and appreciate clear, consistent updates. For many GPs, especially those just starting out, building a strong network of individual LPs is the bedrock of their business, allowing them to fund deals without getting tangled in the red tape of institutional fundraising.

To help GPs better understand these investor archetypes, here's a quick comparison of their typical profiles.

A Comparison of Common LP Profiles in Real Estate

This table compares the typical characteristics of different Limited Partner types to help GPs tailor their fundraising and investor relations strategies.

Ultimately, each type of LP brings something unique to a partnership. The most successful GPs are the ones who learn how to speak the language of all three and build a capital base that aligns with their strategy.

What LPs Look for Before They Invest

Before any serious investor commits millions of dollars to a fund, they're going to kick the tires. Hard. This process, known as due diligence, isn't just a box-ticking exercise; it's a deep, investigative dive to validate everything the General Partner (GP) claims and to uncover the real risks hiding beneath the surface. If you're a GP, knowing what's coming is half the battle for a successful fundraise.

Think about it this way: a prospective LP in private equity is essentially hiring you to be the steward of their capital for the next decade. They aren't just buying a piece of a deal; they're betting on your team, your strategy, and your integrity. Getting ahead of their questions by understanding their mindset is the key to building trust and momentum from day one.

The Four Pillars of LP Due Diligence

Seasoned LPs tend to structure their investigation around four make-or-break pillars. A wobble in any one of these can bring the whole conversation to a grinding halt.

- The Team and Track Record: First and foremost, who are you? What have you done before? LPs will pour over your past deals, not just looking at the wins but understanding the losses. They want to see a clear, consistent history of executing the same strategy you're pitching now, and they'll want proof that you can navigate both bull and bear markets.

- The Investment Strategy: Is your plan to create value clear, credible, and compelling? A vague promise to "buy low and sell high" will get you laughed out of the room. LPs need to see a specific, repeatable playbook for how you source opportunities, underwrite them, add value post-acquisition, and ultimately exit.

- The Economic Terms: Are you eating your own cooking? LPs meticulously analyze the fund's terms to ensure their interests are aligned with the GP's. This means a sharp focus on management fees, the preferred return hurdle, and the carried interest split. They're looking for a structure that heavily incentivizes you to make them money first.

- Operations and Reporting: Can you actually run the business? LPs need absolute confidence in your back office. They expect institutional-grade fund administration, transparent accounting, and professional, timely communication. A slick pitch deck means nothing if the operational side is a mess.

The smartest GPs don't wait for the questions to roll in. They build a comprehensive, easy-to-navigate online deal room from the start. It’s a powerful signal of transparency and operational competence that builds confidence before a single dollar is on the line.

At the end of the day, an LP’s diligence process is all about trust and verification. They're looking for a true partner—someone with not only a brilliant strategy but also the operational chops and unwavering integrity to see it through.

Cracking Open the LP Agreement: What You Really Need to Know

The Limited Partner Agreement, or LPA, is the legal bedrock of your entire investment. Let's be honest, they can be incredibly dense documents, but understanding the core terms is what separates a passive, hope-for-the-best investor from a truly savvy one. This agreement is the rulebook that dictates everything from how money flows to how decisions are made—and most importantly, how and when you get paid.

Think of the LPA as the detailed instruction manual for a complex, multi-year partnership. You wouldn't assemble a sophisticated piece of machinery without reading the manual, and you shouldn't commit millions of dollars without understanding these terms. Getting fluent in this language allows you to see past the sales pitch and analyze the real structure of a deal. You'll quickly learn to spot the difference between an agreement that's stacked in the General Partner's (GP) favor and one that properly protects the LP in private equity.

Decoding the Core Economic Terms

While an LPA covers dozens of clauses and covenants, your net returns are ultimately driven by just a handful of key economic terms. These are the gears of the machine, controlling how fees are charged and profits are split.

- Management Fee: This is the annual fee the GP charges to keep the lights on. It’s typically 1-2% of your total committed capital and covers the fund's operational overhead—think salaries, travel, office space, and all the legwork involved in sourcing and vetting deals before they start producing returns.

- Preferred Return (Hurdle Rate): This is one of the most critical protections for an LP. It establishes a minimum annual return, often set at 7-8%, that LPs must earn on their invested capital before the GP can start taking their share of the profits. In short, it ensures you get paid first.

- Carried Interest (The "Promote"): This is the big prize for the GP. It’s their slice of the fund's profits, almost always 20%, but it only kicks in after LPs have received their initial capital back in full and cleared the preferred return hurdle. This is a powerful incentive that aligns the GP’s success directly with yours; they only make the big money when you do.

A Simplified Distribution Waterfall Example

So, how does this all work in practice? Let's walk through how a hypothetical $100,000 profit would flow through the "distribution waterfall."

- Return of Capital: First things first. Before anyone talks about profit, the LPA makes sure all LPs get 100% of their original investment back. This step has to be completed before the waterfall can flow to the next level.

- Preferred Return: Now, LPs get their "pref." Let's say the fund has $1 million in LP capital and an 8% hurdle rate. Out of our $100,000 profit, the first $80,000 goes straight to the LPs to satisfy that preferred return.

- Carried Interest Split: The LPs' hurdle has been met. The remaining $20,000 in profit is now ready to be split. Under a standard 80/20 arrangement, the LPs receive another $16,000 (80%), and the GP finally earns $4,000 (20%) as their carried interest.

So, at the end of the day, out of $100,000 in total profit, the LPs walked away with $96,000, and the GP took home $4,000. This clearly shows how a well-structured LPA prioritizes getting investors their money back, plus a baseline return, before the manager gets a significant piece of the upside.

The willingness of LPs to commit to these structures remains robust, especially in certain sectors. Private real estate fundraising, for instance, saw a rebound with $222.2 billion raised, marking a 29% increase from the previous year. This signals renewed LP confidence and underscores why it’s so important for GPs managing over $100 million to use professional portals that can handle these complex fund structures. You can discover more insights about this fundraising trend and what it means for the market.

How GPs Attract and Retain the Best LPs

In private equity today, just getting capital in the door is only half the job. The real marker of a successful General Partner (GP) is the ability to not just attract investors, but to keep them coming back, fund after fund. This has never been more critical.

The market is getting tighter. We recently saw global private equity fundraising dip by 11% to $490.81 billion, and that pressure is felt across the board. LPs are becoming far more discerning, often sticking with the big, established GPs they already know and trust. For smaller or emerging managers, this means the fight for every dollar is tougher than ever. You can read the full research about this fundraising decline to get a deeper sense of the landscape.

The Three Pillars of Investor Loyalty

So, how do the best GPs stand out and build a loyal investor base? It’s not about flashy presentations. It’s about nailing the fundamentals, which I like to think of as three core pillars.

- Radical Transparency in Reporting: Today’s LPs expect more than a dense PDF report once a quarter. They want clear, timely, and intuitive access to their information. Think clean investor dashboards showing performance metrics, capital account statements, and even data on individual assets, all available on demand.

- Proactive Communication: Don't make your LPs chase you for information. The best GPs get ahead of the questions. They send out regular, insightful updates on strategy, how market shifts are impacting the portfolio, and the performance of key assets. A simple, well-timed email or a short video update goes a long way in building trust.

- Flawless Operational Execution: From the moment an LP in private equity signs their first subscription document to the day they receive their final distribution, every interaction has to be seamless and professional. Using technology to handle fundraising paperwork, manage accreditation, and process distributions isn't just a nice-to-have anymore; it's table stakes for being seen as a credible operator.

The best GPs make their investors feel like true partners, not just entries in a spreadsheet. This means creating a frictionless experience that inspires confidence and makes it easy for LPs to reinvest in future deals.

To get in front of the right people, GPs can use dedicated platforms to search for investors and manage those crucial early conversations. By building a business on a foundation of transparency, communication, and operational excellence, GPs can set themselves apart and build the kind of loyalty that lasts through any market cycle.

Got Questions About Being an LP? We've Got Answers.

Stepping into the world of private equity can feel like learning a new language. Whether you're a new investor figuring out the landscape or a GP trying to manage these critical relationships, a few questions always seem to pop up. Let's break down some of the most common ones about the role of an LP in private equity.

What’s the Real Difference Between an LP and a GP?

At its heart, the difference comes down to two things: control and liability. A Limited Partner (LP) is the one who brings the money to the table. They write the checks, but their risk is capped—they can’t lose more than the capital they’ve committed. Most importantly, they are hands-off when it comes to running the fund.

A General Partner (GP), on the other hand, is the one in the trenches. They’re making the investment decisions, managing the portfolio companies, and are ultimately responsible for the fund's performance. The GP has unlimited liability. A simple way to think about it is this: the LP is the silent financial backer, while the GP is the active manager steering the ship.

How Much Say Does an LP Actually Get?

Very little, at least when it comes to day-to-day decisions. An LP's influence is strongest at the very beginning—during the due diligence phase when they're deciding which GP to back. After that, their power is defined by the terms negotiated in the Limited Partner Agreement (LPA).

Some sophisticated LPs might negotiate for a seat on an advisory committee or secure voting rights on major decisions, like extending the life of the fund. But make no mistake, the GP always has the final say on operational matters. For an LP, the single most critical decision is picking a GP they trust implicitly with their capital.

What Happens if an LP Can’t Make a Capital Call?

Failing to meet a capital call is a huge deal. It’s not just a missed payment; it jeopardizes the GP’s ability to close on a time-sensitive investment. Because of this, the penalties laid out in the LPA are designed to be severe.

Consequences are intentionally harsh. You could be forced to forfeit a significant chunk of your existing investment, lose any claim to future profits, or even have your stake sold off to other partners at a steep, punitive discount.

Can an LP Cash Out Early?

Private equity is built for the long haul. When you invest, you're agreeing to lock up your capital for seven to ten years, sometimes even longer. There’s no "sell" button like you’d find with public stocks.

That said, an exit route does exist. LPs can sometimes sell their interest in what’s known as the secondary market. This isn't a simple process; it's a private transaction that requires the GP's approval. The secondary market has matured a lot over the years, providing a legitimate—though not always easy—option for LPs who find themselves needing liquidity before the fund officially wraps up.

Ready to build stronger investor relationships and streamline your fundraising? Homebase provides an all-in-one platform for real estate syndicators to manage deal rooms, investor updates, and distributions with ease. See how Homebase can simplify your operations.

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

DOMINGO VALADEZ is the co-founder at Homebase and a former product strategy manager at Google.

What To Read Next

A Syndicator's Guide to the Sales Comparison Approach

Blog

Master the sales comparison approach in real estate syndication. Learn to find comps, make data-driven adjustments, and build investor confidence.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

© 2026 Homebase. All rights reserved.