Structure of Private Equity Fund: The Ultimate Guide

Structure of Private Equity Fund: The Ultimate Guide

Explore the structure of private equity fund: a clear overview of entities, waterfalls, and governance.

Domingo Valadez

Dec 21, 2025

Blog

Think of a private equity fund's structure like a custom-built home. You have the architect and the general contractor—the General Partner (GP)—who designs the blueprint, pours the foundation, and manages the entire construction. Then you have the investors—the Limited Partners (LPs)—who provide the financing to bring the project to life.

It's a powerful partnership that matches operational expertise with the capital needed to acquire and improve assets, all for a shared profit.

Building Your Fund: A Blueprint for Success

At its heart, a private equity fund is just a vehicle for pooling money from multiple investors to buy something big, like a commercial real estate portfolio. This setup creates a clean division of labor and, just as importantly, liability. It’s what makes large-scale projects possible when they’d be out of reach for any single investor. The whole system really runs on a foundation of trust and aligned incentives.

The General Partner (GP) is the operator in the trenches. This is the real estate syndicator or sponsor who finds the deals, runs the numbers, gets the loan, manages the asset, and ultimately, sells it for a profit. It's an active, hands-on job that demands serious industry knowledge and operational chops.

On the other side of the table, you have the Limited Partners (LPs). These are the passive investors who write the checks, providing most of the equity for the deal. Their job is to supply the capital; in return, they expect a healthy profit without having to deal with any of the day-to-day headaches of property management.

The Two Pillars of a Fund Structure

This GP/LP dynamic is the engine that drives the private equity world. It’s an incredibly efficient way to connect capital with expertise. To make it all work smoothly, you need a solid legal and economic framework that spells out everyone's roles and rewards.

The key components of this blueprint include:

- The Players: A clear line between the active manager (the GP) and the passive investors (the LPs).

- The Legal Entities: Using specific structures like Limited Partnerships and LLCs to shield everyone involved from unnecessary liability.

- The Economic Terms: The "deal" itself—how the GP gets paid for their work and how profits are split with investors.

- The Documentation: The legal agreements that serve as the operating manual for the fund, from start to finish.

This separation of roles is what makes the model so powerful. LPs get access to professionally managed, high-quality real estate deals they could never find or run themselves. GPs, in turn, get to scale their business by putting investor capital to work.

Getting this foundational concept right is the first major step for any syndicator thinking about moving from one-off deals to a more scalable fund model. The private equity structure gives you the roadmap to pool capital efficiently, manage risk properly, and build a repeatable system for buying and profiting from real estate.

The Legal Architecture of a Private Equity Fund

Before a dollar is raised or a property is acquired, you need a rock-solid legal framework. A private equity fund's structure isn't just about shuffling papers; it's the very foundation that protects everyone involved, aligns incentives, and ensures capital flows where it needs to go. Think of it as the plumbing and wiring of your deal—hidden from view but absolutely essential for making everything work.

At the heart of almost every real estate fund, you'll find the Limited Partnership (LP). This isn't a new invention; it's been the industry gold standard for decades for one simple reason: it perfectly separates the active manager from the passive investors. This formal distinction is the key to managing both liability and operations effectively.

The Limited Partnership is built on two very different roles: the General Partner and the Limited Partners. Getting this dynamic right is fundamental to your success. To get a more granular look at how these roles play out, check out our guide on the https://www.homebasecre.com/posts/gp-lp-structure for real estate.

The General Partner and the Liability Shield

The General Partner (GP) is the one in the driver's seat. They're the deal finders, the asset managers, and the ones executing the business plan day in and day out. But in a standard partnership, that active role comes with a terrifying catch: unlimited personal liability. If the deal went sideways, the GP's personal assets could be on the line.

No experienced sponsor takes that risk. Instead, the GP almost always forms a separate entity—usually a Limited Liability Company (LLC)—to serve as the official General Partner of the fund. This simple step creates a crucial liability shield. Now, if a major lawsuit hits the project, it hits the LLC, not the sponsor's personal bank account. Understanding how professionals legally organize to manage risk, including through structures like Limited Liability Partnerships (LLPs), provides valuable context.

Key Takeaway: The GP is the "brains" of the operation, making all active decisions. The LPs are the "capital," providing the fuel for the fund's investments while remaining passive and protected from day-to-day liabilities.

The Limited Partners (LPs) are your investors. Their job is to provide the capital, and that's it. They have no say in the day-to-day management of the fund, which is exactly how they want it. In exchange for taking this passive role, their liability is "limited" to the amount of money they put in. They can't lose a penny more than their initial investment, which is a powerful and necessary protection for anyone writing a check.

Before we move on, let's quickly summarize the key players we've just discussed and their distinct roles.

Key Roles in a Private Equity Fund Structure

This table clarifies how each piece fits together to create a structure that is both functional and secure for all parties.

Using Special Purpose Vehicles for Asset Protection

Most sophisticated fund structures don't stop there. They add another layer of protection known as a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV). An SPV is just a separate legal entity, almost always an LLC, created for the sole purpose of owning one specific asset.

Let's say your fund plans to buy three different apartment buildings. Instead of the main fund entity owning all three properties directly, the GP will create a unique SPV for each one. This compartmentalizes the risk.

- SPV 1: Holds Apartment Building A

- SPV 2: Holds Apartment Building B

- SPV 3: Holds Apartment Building C

Think of this like the watertight compartments on a ship. If a major lawsuit or financial crisis sinks Apartment Building A, the disaster is contained within SPV 1. The other two properties and the main fund itself are legally walled off from the problem. This asset-level separation is a non-negotiable part of professional risk management in real estate private equity.

How Everyone Gets Paid: The Distribution Waterfall

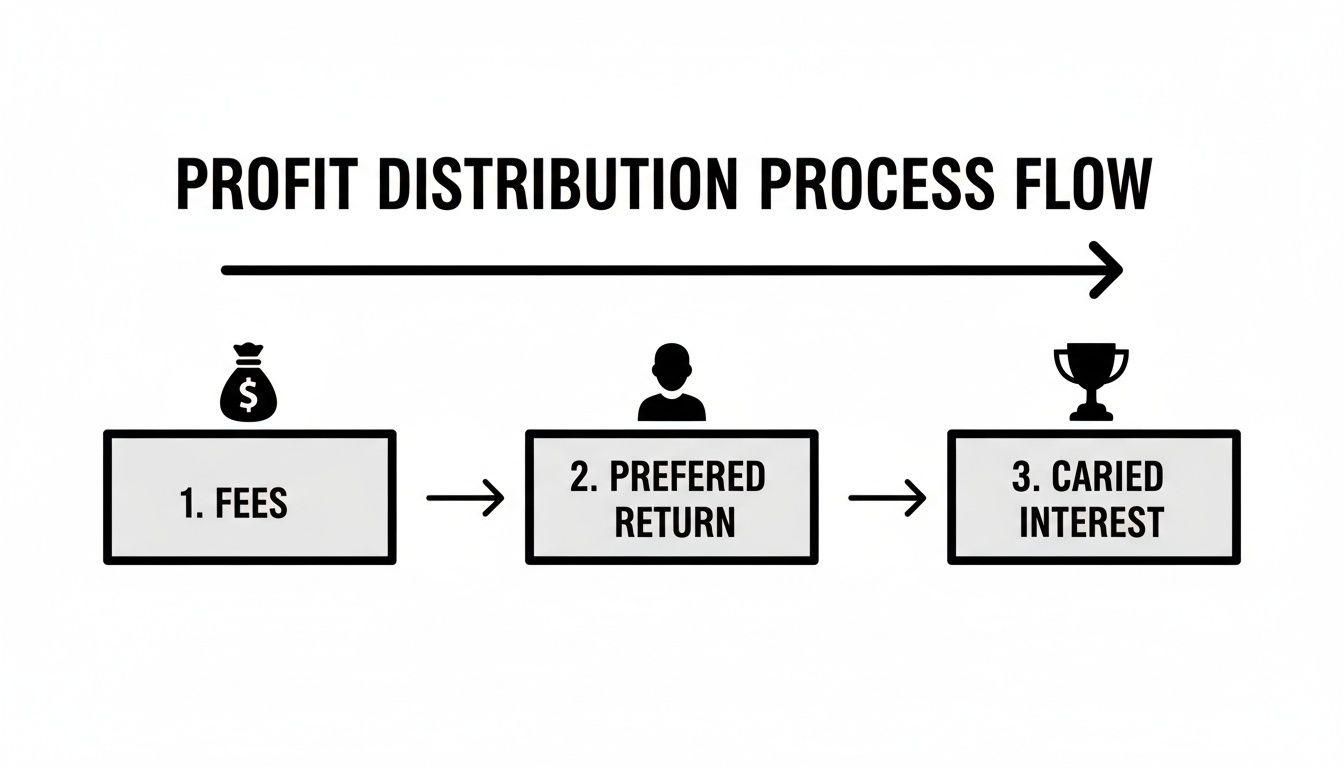

Once you’ve got the legal entities sorted out, it’s time to talk about the money. This is where the rubber meets the road—the economic structure that spells out exactly how cash flows back to your investors and, eventually, to you. The entire system hinges on a mechanism called the distribution waterfall.

Picture a series of champagne glasses stacked in a pyramid. You pour champagne into the top glass, and only when it’s completely full does it spill over to fill the glasses in the next row down. That's a distribution waterfall, in a nutshell. It's a tiered system that dictates who gets paid, in what order, ensuring profits are distributed fairly and predictably. For any real estate syndicator, getting this right is non-negotiable.

Tier 1: The Management Fee

Before anyone even thinks about profits, the fund has to keep the lights on. The management fee is the first tier, designed to cover the day-to-day operational costs of running the fund. We're talking about salaries, office space, legal bills, accounting services, and all the overhead that comes with sourcing, underwriting, and managing real estate assets.

This fee is almost always calculated as a small percentage—typically 1% to 2%—of the total capital investors have committed. It’s usually paid out quarterly or annually and is the lifeblood of the operation. Think of it as the cost of doing business; it ensures you have the resources to actually execute the strategy you pitched to your investors.

Tier 2: The Preferred Return

With the bills paid, the next glass to be filled belongs exclusively to your investors. This is the preferred return, often called the "pref" or "hurdle rate." It’s the first cut of the profits, and it all goes to the Limited Partners (LPs). Consider it a minimum performance bar you, the General Partner (GP), have to clear before you can share in the upside.

This is a crucial investor protection. It guarantees that LPs get their initial capital back, plus a predetermined return, before the GP earns a dime of performance-based pay.

A common preferred return in the real estate world lands somewhere between 6% and 8% annually. Until every LP has received distributions equal to their original investment plus this compounding return, 100% of the distributable cash flows straight to them. This tier is great for aligning interests because it forces you to generate a solid, baseline return for your partners first.

And investors are paying closer attention to this than ever. Recent industry surveys show that LPs now rank DPI (Distributions to Paid-In Capital) as a critical metric 2.5 times more than they did just three years ago. This shift is a big deal and directly impacts how GPs think about structuring their funds. You can learn more about the latest private equity trends shaping these deals.

Tier 3: The Catch-Up and Carried Interest

Only after the LPs' preferred return is fully satisfied does the champagne finally spill over into the GP's glass. This is where your performance compensation, known as carried interest or the "promote," comes into play. Carried interest is your share of the fund's profits, and it's the primary incentive for knocking a deal out of the park.

The industry standard is a "20% carry," meaning the GP gets 20% of the profits. But it's not quite that simple. To make sure the final split is a true 80/20 of all profits (after the return of capital), most waterfalls include a catch-up provision.

Here’s how that catch-up works in practice:

- Preferred Return Paid: First, all profits go to the LPs until their pref is met.

- GP Catch-Up: Next, 100% of the profits go to the GP until they have "caught up" on what would have been their 20% share of the profits distributed so far.

- The Final Split: From that point on, all remaining cash is split according to the agreed-upon carry structure—most commonly, 80% for the LPs and 20% for the GP.

Let’s run through a quick example to make this crystal clear.

A Waterfall in Practice: A $10 Million Example

Let's say you raise $10 million from LPs for a deal. The terms are an 8% preferred return and a 20% carried interest for you, the GP. A few years later, you sell the property and have $14 million in cash ready to distribute.

Here’s how the money would flow through the waterfall:

- Return of Capital: The first $10 million goes right back to the LPs to return their initial investment.

- Preferred Return: The next $800,000 ($10M x 8%) goes to the LPs to satisfy their pref. Now, the LPs have received a total of $10.8 million.

- GP Catch-Up: Your 20% share of that $800,000 profit is $160,000. So, the next $160,000 in profit goes 100% to you to "catch up."

- Final 80/20 Split: Now we figure out what's left. We started with $14M and have paid out $10.96M ($10M + $800k + $160k). That leaves $3.04 million. This final amount is split 80/20.LPs Receive: 80% of $3.04M = $2,432,000GP Receives: 20% of $3.04M = $608,000

When all is said and done, the LPs get their $10M back plus a total profit of $3,232,000 ($800k + $2.432M). You, the GP, earn a total of $768,000 ($160k + $608k) in carried interest. This step-by-step process ensures everyone gets paid fairly based on the deal's performance.

Raising Capital and Putting It to Work

A solid legal framework and a fair economic structure are essential, but a fund is just an idea on paper until investors actually commit their money. This is where we get into the operational mechanics of gathering capital and deploying it into assets—a process that's crucial for setting investor expectations and managing the fund’s lifecycle.

The journey from idea to investment starts with the subscription process. You can think of this as the formal "RSVP" from your investors. After they’ve done their homework and reviewed your legal documents (like the Private Placement Memorandum, or PPM), an interested Limited Partner (LP) signs a subscription agreement. This is the legally binding document where they commit a specific amount of capital to your fund.

From Commitments to Closings

This initial pledge is known as committed capital. It’s the total amount of money an LP has agreed to invest, but here's the key: they don't just write you a check for the full amount on day one. Instead, that capital sits on the sidelines, ready to be called upon the moment you find a great deal.

You'll accept these subscriptions during a defined fundraising window marked by closings. A fund might have a "first close" once it hits a minimum target, which gives you the green light to start buying properties. You can then continue accepting new investors in later closings until you reach your "final close," which is the hard stop for fundraising.

Once this capital is put to work and starts generating returns, the profit distribution kicks in.

This flow shows how operational fees are paid first, then investors get their preferred return, and only after those hurdles are cleared does the General Partner earn their performance-based carried interest.

The Power of Capital Calls

So, you’ve found a great property that fits your fund's strategy and you get it under contract. What's next? You initiate a capital call. This is a formal notice sent to all your LPs requesting a specific portion of their committed capital. For example, if an LP committed $200,000 and you issue a call for 25% of commitments, they are legally required to wire you $50,000 by a set deadline.

This is the moment committed capital becomes invested capital—real cash used to acquire the property. It's an incredibly efficient, "just-in-time" funding model. It lets you, the GP, access huge sums of money precisely when you need it without having idle cash sitting around dragging down the fund's overall returns.

Key Takeaway: Investors commit a total amount upfront but only send money when the GP finds a specific deal. This "just-in-time" capital funding mechanism is a hallmark of the private equity fund structure.

Breaking into this world isn't always easy for new managers, though. The private equity structure tends to favor larger, more experienced GPs. The top 10 funds recently captured a massive 36% of all capital raised, with a staggering 98% of capital flowing to seasoned fund managers. This really shows how much LPs value a proven track record, especially when fundraising gets tough. You can discover more insights on private equity fundraising trends on bain.com.

Mapping the Fund Lifecycle

This whole process plays out over a clearly defined timeline, usually broken down into two main phases.

- The Investment Period: This is your active "hunting" phase, typically lasting the first two to four years. During this time, your main job as the GP is to source deals, perform due diligence, and use capital calls to acquire properties for the fund's portfolio.

- The Harvesting Period: After the Investment Period closes, your focus shifts entirely. Your role transitions from acquiring to actively managing the assets. You'll execute the business plan—things like renovations, increasing rents, and improving operations—with the ultimate goal of selling the properties. This is when you "harvest" the returns and distribute profits back to the LPs through the waterfall structure we covered earlier.

This predictable lifecycle gives everyone involved a clear roadmap. It sets a timeline for when capital will be called, when value will be created, and when profits can be expected, bringing much-needed structure and discipline to the entire investment.

Understanding Your Fund's Core Legal Documents

A well-structured fund isn't just about a great strategy; it's built on a foundation of solid legal paperwork. These documents are your fund’s operating system. They define the rules of the road, protect you and your investors, and create the trust needed to manage other people’s money successfully.

For any syndicator launching a fund, you're going to live and breathe by three core legal documents. Let's think of them as the constitution, the business plan, and the VIP amendments for your key partners.

The Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA)

First and foremost is the Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA). This is the big one—the single most critical document in your fund. It’s the definitive legal contract that binds you, the General Partner (GP), and your investors, the Limited Partners (LPs).

If your fund is a business, the LPA is its constitution. It spells out every single detail of how the fund will operate, leaving nothing to chance.

Key terms you'll find hammered out in the LPA include:

* The Economics: How you get paid (management fees), the investors' hurdle rate (preferred return), and your profit share (carried interest).

* Rights and Powers: What you can and can’t do as the GP, and what rights the LPs have.

* Mechanics of the Fund: The nitty-gritty on how you’ll call capital, make distributions, and how long the fund will last.

* Reporting Requirements: Your specific obligations for keeping investors updated with financial statements and progress reports.

Every single investor signs onto this agreement. It’s designed to be exhaustive, so when questions or disagreements come up later, you have a clear rulebook to turn to.

The Private Placement Memorandum (PPM)

While the LPA is the internal rulebook, the Private Placement Memorandum (PPM) is the formal document you give to prospective investors. Think of it as your fund's official resume and business plan, all rolled into one comprehensive package.

The PPM lays out the entire investment opportunity, from your strategy and the market you're targeting to the bios of your team. Critically, it also includes a thorough discussion of the potential risks. You need to be upfront and transparent here.

The PPM's most important job is legal protection. By disclosing all the material information and potential risks, you’re complying with securities laws and protecting yourself from future claims that you misled investors.

A professional, well-written PPM shows you’re a serious operator. It builds instant credibility and gives investors the confidence they need to write a check.

Side Letters for Key Investors

Finally, let's talk about Side Letters. These aren't for everyone. A side letter is a separate legal agreement that tweaks the terms of the LPA for a specific, important investor.

You'll typically use these to land a large, "anchor" investor who has the leverage to ask for special treatment. They don't want to change the rules for everyone, just for themselves.

What kind of special terms might they negotiate?

* Fee Breaks: A slightly lower management fee or a better deal on the carried interest.

* Co-Investment Rights: The opportunity to invest extra capital directly into a specific deal alongside the fund, giving them more exposure to your best assets.

* More Information: A request for more frequent or more detailed financial reporting.

Side letters are your tool for flexibility. They allow you to accommodate the unique needs of a cornerstone partner without having to rewrite the entire LPA, making them a powerful part of your fundraising toolkit.

Tweaking the Classic Fund Model for Today’s Market

The classic private equity fund structure is a fantastic starting point, but let's be honest—it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution. In a market this competitive, the sharpest real estate sponsors know that flexibility is key. They're constantly adapting the traditional model to attract a wider net of capital partners and make sure everyone's interests are truly aligned.

Two of the most common and powerful ways to do this are through co-investments and Separate Managed Accounts (SMAs). Think of these as tools in your toolbox. They give sophisticated investors more direct control, better economics, and a bespoke way to invest, which can make your fund offering incredibly compelling. If you're a sponsor looking to stand out, you need to know how these work.

Giving LPs More Skin in the Game with Co-Investments

So, what is a co-investment? It’s simply an opportunity for your Limited Partners (LPs) to invest directly into one of your specific deals, right alongside the main fund.

Let’s play this out. Say your fund is putting $5 million into acquiring a new apartment building. You could then turn to a few of your biggest LPs and offer them the chance to put an extra $2 million directly into that property's SPV.

It’s a true win-win. Your LPs get to double-down on an asset they really believe in, and they often get a major break on the fees—sometimes paying heavily reduced or even zero management fees and carried interest on that extra capital. For you, the General Partner (GP), it’s a brilliant way to cement relationships with your best investors and tackle bigger deals without draining the main fund.

Co-investments build powerful alignment. By allowing LPs to "double down" on their favorite deals, you give them more control and better economics, deepening their partnership with your firm.

This isn't some niche strategy anymore; it's become standard practice. Private equity funds now frequently build in co-investment rights, which often amount to around 20% of a fund's total size. A $10 billion fund, for instance, might facilitate another $2 billion in co-investments. For real estate syndicators, offering these kinds of side-car deals can be what sets you apart from the crowd. You can read the full research about private capital trends on mckinsey.com.

Matching the Structure to the Strategy

It's not just about individual deals; you can adapt the entire fund's approach. Different real estate strategies come with different levels of risk, and your fund's structure needs to reflect that reality. Smart sponsors often create distinct funds or SMAs built around specific risk-return profiles:

- Core Strategy: This is your bread and butter—stable, cash-flowing properties in great locations, like a fully leased office tower in a downtown core. The structure here is usually plain vanilla, with lower fees and a target return that’s modest but reliable.

- Value-Add Strategy: Here, you're buying properties that need a little TLC, maybe some light renovations or better management. The risk is a step up, so the structure might look more traditional with a standard 8% preferred return and a 20% carry for the sponsor.

- Opportunistic Strategy: This is the high-stakes table. We're talking ground-up development or turning around a truly distressed asset. To compensate for that level of risk, the structure needs to offer investors a higher preferred return, and the GP might get a larger slice of the carried interest.

When you tailor the fund structure to the specific strategy, you're not just creating a deal—you're building a logical, compelling case for why an investor should trust you with their capital.

Common Questions About Private Equity Fund Structures

Even with the best blueprints, moving from theory to practice always brings up questions. Let's tackle some of the most common ones we hear from real estate sponsors and investors getting into the fund world.

How Is a Fund Different From a Real Estate Syndication?

Think of it this way: a real estate syndication is like buying a ticket for a specific, pre-scheduled flight. You know the exact destination—the asset—before you put your money down. Investors are backing a single, identified property.

A private equity fund, on the other hand, is more like giving your money to an experienced pilot who has a clear flight plan but hasn't picked the exact destinations yet. You're investing in the General Partner's strategy and their ability to find multiple great assets over time. Investors contribute to a "blind pool" of capital, gaining portfolio diversification instead of single-asset focus.

Why Is the 2 and 20 Fee Structure So Common?

The classic "2 and 20" model has stuck around for a reason: it creates a powerful alignment of interests. The two pieces work together to keep the whole operation running smoothly.

The "2% management fee" is the operational fuel. It covers the GP's overhead—salaries, office space, marketing, legal—so they can dedicate their full time and resources to sourcing, underwriting, and managing deals. It keeps the lights on.

The "20% carried interest" is the performance engine. This is the GP's share of the profits, but it only kicks in after investors have received their preferred return. It's the ultimate incentive for the GP to not just meet expectations, but to knock it out of the park. They only make serious money if their investors make great money first.

This dual structure provides the GP with stability while tying their biggest rewards directly to investor success. It's a true partnership model focused on a shared goal: generating outstanding returns.

Can the Terms in a Limited Partnership Agreement Be Negotiated?

Technically, yes, but it’s a privilege usually reserved for the heavy hitters. Large institutional investors—think pension funds or endowments—can use the power of their multi-million dollar checks to negotiate special terms through what's called a "side letter."

A side letter is essentially a private amendment to the main Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA) that applies only to that specific investor. They might secure a small fee reduction, enhanced reporting, or first dibs on co-investment opportunities. For the vast majority of individual investors, however, the terms laid out in the LPA are presented on a take-it-or-leave-it basis.

Ready to streamline your next deal? Homebase provides an all-in-one platform for real estate syndicators to manage fundraising, investor relations, and distributions, all with predictable, flat-rate pricing. Simplify your operations and focus on what matters most—closing deals. Learn more and get started at https://www.homebasecre.com/.

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

DOMINGO VALADEZ is the co-founder at Homebase and a former product strategy manager at Google.

What To Read Next

A Guide to Real Estate Financial Modelling for Syndicators

Blog

Master real estate financial modelling with this guide. Learn to build models that analyze deals, forecast returns, and build unwavering investor confidence.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

© 2026 Homebase. All rights reserved.