Guide: difference between limited and general partnership for RE syndicators

Guide: difference between limited and general partnership for RE syndicators

Explore the difference between limited and general partnership and how it protects investors while streamlining real estate fundraising.

Domingo Valadez

Jan 7, 2026

Blog

When you're structuring a real estate deal, the difference between a limited and general partnership isn't just a legal detail—it's the core of how you'll manage liability and responsibility. At its heart, a Limited Partnership (LP) is designed to protect passive investors from the business's debts and legal troubles. A General Partnership (GP), on the other hand, puts every partner on the hook with unlimited personal liability. For anyone trying to raise capital in real estate, this distinction changes everything.

Comparing Partnership Structures For Real Estate Deals

Picking the right legal entity is one of the most critical moves a real estate sponsor makes right out of the gate. This decision sets the stage for your legal exposure, how you'll pitch the deal, and the way you'll manage your investor relationships for years to come. While they both fall under the "partnership" umbrella, the way LPs and GPs function in the real estate world couldn't be more different.

Think of a General Partnership as a structure built on total collaboration and shared risk. Every partner gets a vote in the day-to-day decisions, but they also share personal responsibility for every single business debt. It can work for a small, tight-knit group of two or three active developers, but it quickly becomes a liability nightmare when you start bringing in capital from passive investors who aren't involved in operations.

This is where the Limited Partnership shines, as it's practically tailor-made for the syndication model. The LP structure cleanly divides partners into two distinct roles:

- General Partners (GPs): This is you—the sponsor or management team. You run the show, make the decisions, and in return, you take on unlimited liability for the project.

- Limited Partners (LPs): These are your passive investors. They provide the capital you need to get the deal done, but their involvement stops there. Crucially, their liability is limited to the exact amount of money they put into the deal.

That clear separation of duties and liability is precisely why the LP has become the gold standard in real estate syndication. It gives sponsors the control they need to execute their business plan while offering investors the kind of protection they expect.

Quick Comparison: Limited Partnership (LP) vs. General Partnership (GP)

To put it all in perspective, let's break down the key differences between these two structures from a syndicator's point of view. This table cuts straight to what matters most: liability, management authority, and fundraising capabilities.

The numbers really drive home why the LP is so powerful for capital-intensive projects. According to IRS statistics for 2023, LPs accounted for just 9.7% of all partnerships but were responsible for an astonishing $689.1 billion in pass-through income. This structure's unique ability to pool large amounts of capital while safeguarding investors makes it the clear winner for serious syndicators.

For a deeper dive into this topic, be sure to check out our complete guide on real estate syndication structures.

Analyzing Liability and Management Roles

When you peel back the layers of partnership structures, the core differences between a limited and a general partnership really come down to two things: liability exposure and management control. These aren't just legal buzzwords; they have massive, real-world consequences that can make or break a deal, protect or expose your investors' personal assets, and dictate how effectively you can run the show. Honestly, getting this right is non-negotiable before you even think about raising capital.

In a General Partnership (GP), liability is a shared burden, and it’s absolute. Every partner is considered an agent for the entire group, so the actions of one person legally bind everyone else. The truly alarming part is the unlimited personal liability that comes with it, a concept lawyers call "joint and several liability."

What this means is if the partnership gets sued or can't pay its bills, creditors can come after the personal assets of any partner to cover the full debt. We're talking about their homes, cars, and savings—and it doesn't matter if they only owned a tiny slice of the deal.

The Perils of Unlimited Liability in Real Estate

Let’s play this out. Say you’re renovating a multifamily property under a GP structure. You hit a major snag—unexpected structural problems—and your budget is suddenly $500,000 in the red. If the partnership’s cash reserves are gone, the contractors and lenders can legally go after any partner’s personal bank account to get paid.

It gets worse. Imagine a tenant is seriously injured on the property and wins a lawsuit that blows past your insurance limits. In a GP, every single partner's personal wealth is fair game to satisfy that judgment. This level of exposure is precisely why the GP model is a non-starter for syndications with passive investors.

In a General Partnership, a partner with just a 1% stake can be held personally responsible for 100% of the partnership's debts. This disproportionate risk is precisely why sophisticated investors avoid this structure for passive investments.

The Limited Partnership Liability Shield

This is exactly the problem the Limited Partnership (LP) was designed to solve. It erects a legal firewall, separating the business's liabilities from the personal assets of the passive investors (the limited partners).

In an LP, their financial risk is capped at the exact amount of capital they invested. If the project goes south and racks up huge debts, they might lose their entire investment, but their personal finances are safe. This protection is the foundation of real estate syndication; it’s the main reason investors feel comfortable putting their capital into these deals.

Of course, the General Partner (that’s you, the syndicator) still has unlimited liability. But there’s a standard workaround for this: syndicators almost always form a separate entity, like an LLC, to serve as the General Partner. This move effectively shields their personal assets, too.

Clarifying Management Authority and Control

The other critical distinction is how management works. A GP typically runs like a democracy, where every partner gets an equal say in decisions unless the agreement states otherwise. This might be fine for a simple two-person venture, but it’s a recipe for disaster when you have dozens of investors.

Can you imagine trying to get a sign-off from 50 different partners on every key decision, from hiring a new property manager to approving a major roof repair? It's a logistical nightmare that would bring any project to a grinding halt.

An LP cuts through that chaos by centralizing control. The roles are crystal clear:

* The General Partner has the exclusive authority to run the day-to-day operations and make all strategic decisions.

* The Limited Partners are legally prohibited from participating in management. Their role is purely passive.

This clear-cut division of labor is essential. It gives the syndicator the power to execute the business plan without endless committee meetings. At the same time, it assures investors that a designated expert is at the helm, managing their capital without interference from a crowd. This isn't just about being efficient—it's about aligning roles with expectations, which is fundamental to building and maintaining investor trust.

Comparing Tax Implications and Profit Distributions

When you’re weighing a limited partnership against a general one, how you handle taxes and distribute profits is a massive deciding factor for any real estate syndicator.

Both structures offer a huge advantage right out of the gate: pass-through taxation. This is a big deal. It means the partnership itself doesn’t get hit with corporate income tax. Instead, all the profits and losses flow directly through to the partners, who then report them on their personal tax returns.

This setup lets you sidestep the dreaded "double taxation" you see with C-corps, where the business pays taxes on its income, and then shareholders pay taxes again on their dividends. But while both LPs and GPs share this core benefit, the way profits, losses, and tax burdens are actually divided up couldn't be more different.

Profit Distribution Models: Pro-Rata vs. Performance-Based

In a General Partnership, the default method for splitting profits is painfully simple, and frankly, a bit rigid. Unless you’ve drafted a highly customized partnership agreement, profits and losses are usually split pro-rata. It’s straight math—if you own 20% of the partnership, you get 20% of the profits.

This works just fine for a simple joint venture between a couple of active partners, but it completely falls apart in the real world of real estate syndication. Syndicators need to attract different types of investors and, just as importantly, need to be rewarded for their performance. The pro-rata model just doesn't offer that kind of nuance.

This is where the Limited Partnership really shines. An LP is built for flexibility, and the partnership agreement becomes your playbook for creating sophisticated, multi-tiered profit distribution models called distribution waterfalls.

A waterfall structure allows you to design a payment hierarchy that perfectly aligns the sponsor's (the General Partner) interests with the investors' (the Limited Partners). A typical waterfall in a real estate deal might look something like this:

- Return of Capital: First, every dollar of distributable cash goes to the Limited Partners until their initial investments are paid back in full.

- Preferred Return: Once capital is returned, investors start earning their "pref"—a fixed annual return (say, 8%) on their investment. The sponsor doesn't see a dime of the profit split until this hurdle is cleared.

- Catch-Up Provision: This is a tier that allows the sponsor to receive a larger share of the profits for a period, letting them "catch up" to a predetermined split.

- Carried Interest: After all the lower hurdles are met, the remaining profits are split between the LPs and the GP based on a predefined ratio, like 70/30 or 80/20.

A distribution waterfall is more than a payment schedule; it's a strategic tool. It reassures investors their capital is prioritized while giving the sponsor a powerful incentive to outperform projections, creating a true win-win scenario.

The Role of Basis in Tax Liability

For tax purposes, you have to understand a partner's "basis," which is essentially their economic investment in the partnership. Your basis is what determines how much of the partnership's losses you can deduct on your taxes and whether the distributions you receive are tax-free.

In both GPs and LPs, your basis starts with the cash you put in. But here’s where liability comes back into play and really changes the calculation. In a GP, because every partner has unlimited liability, each partner can increase their basis by their share of the partnership’s debt. This often allows them to deduct much larger losses.

It’s a different story in an LP. Only the General Partner can typically add partnership debts to their basis because they're the one on the hook for those liabilities. Limited Partners usually can't, which caps the losses they can deduct at the amount of their investment. This is the fundamental trade-off for getting that coveted liability protection.

Going beyond the basics of liability and management, a deep dive into various real estate investment tax strategies can make a huge difference to your bottom line. The inherent flexibility of an LP gives sponsors the power to structure deals that are not just operationally sound but also incredibly tax-efficient for everyone involved, making it the clear winner for virtually every real estate syndication.

How Your Partnership Choice Shapes Fundraising and Investor Trust

Choosing between a limited partnership (LP) and a general partnership (GP) is more than just a box to check on a legal form. It’s one of the most fundamental marketing decisions you’ll make. The structure of your deal is one of the first things savvy investors will look at, and it sends a powerful message about your professionalism, how you view risk, and how much you value their capital.

For nearly every passive investor out there, the conversation starts and stops with liability. They are writing a check to get in on the upside of your deal, not to gamble their personal net worth. This makes the unlimited personal liability baked into a General Partnership an immediate deal-breaker for almost every accredited and non-accredited investor you'll meet.

In today's real estate syndication world, trying to raise serious capital with a GP structure is a non-starter. Investors don't just prefer the liability shield of a Limited Partnership; they expect and demand it. It's the baseline requirement for building the trust you need to even get them to look at your offering.

Getting Inside the Head of a Passive Investor

To be a successful fundraiser, you have to think like your passive investors. They're motivated by two things: generating a return and preserving their capital. They want to do this with minimal personal risk and without getting bogged down in day-to-day operations. They are trusting you, the sponsor, with their hard-earned money because they believe you have the expertise to run the show.

The Limited Partnership structure is perfectly built for this mindset. It draws a clear, legally-enforced line in the sand.

- Their Risk is Capped: An investor in an LP knows that the absolute most they can lose is the money they put in. This defined risk makes the decision to invest feel manageable and quantifiable.

- Their Role is Passive: The structure itself legally prevents them from being dragged into management calls, which is exactly what they're paying you to handle.

- Their Trust is Earned: Choosing an LP demonstrates that you're following industry best practices and are serious about protecting your partners. That builds incredible credibility.

A GP, on the other hand, tramples all over these core investor expectations. It introduces undefined, unlimited risk and implies they need to be actively involved, which signals a real lack of sophistication on your part as the sponsor.

The legal structure of your deal is a core part of your pitch. A Limited Partnership tells investors, "Your capital is protected." A General Partnership says, "You're just as exposed as I am." For fundraising, only one of those messages actually works.

Building a Fundraising Machine That Can Scale

Beyond just investor psychology, the operational differences become stark when you try to grow. A typical syndication can involve dozens, sometimes hundreds, of passive investors. An LP is specifically designed to handle this kind of volume with professional efficiency.

With an LP, the syndicator (acting as the General Partner) can build a centralized, streamlined fundraising process. You can set up a secure online deal room, manage digital subscription documents, and onboard new investors with ease. The whole process is standardized because every limited partner shares the same passive role and limited liability.

Now, just try to imagine doing this with a General Partnership. Every single new investor is technically a new general partner with equal management rights and full liability. It’s an administrative catastrophe waiting to happen.

- Decision-Making Paralysis: How could you possibly get operational approval from 75 different general partners on every key decision?

- Onboarding Nightmare: Each new partner would require complex amendments to the partnership agreement just to define their role and responsibilities.

- Liability Chaos: Adding more general partners just multiplies the risk across the board. The poor judgment of one partner could put the personal assets of all the others on the line.

The LP structure provides the clarity, simplicity, and scalability you need for modern real estate syndication. It creates a clean, one-to-many relationship between you and your investors, making it the only practical choice for anyone serious about raising significant capital.

Understanding Formation and Compliance Requirements

When it comes to actually setting up a partnership, the legal and administrative path for a General Partnership (GP) is a world apart from the structured, protective framework of a Limited Partnership (LP). For any real estate syndicator, these differences aren't just red tape—they're the bedrock of investor protection and operational clarity.

A General Partnership can spring into existence with almost startling ease, and sometimes, completely by accident. If two or more people agree to co-own a business and share profits and losses, a GP is born. That agreement can be as simple as a handshake. While that sounds easy, it’s a dangerous trap because it automatically saddles all partners with unlimited personal liability, often with no formal paperwork to define anyone's roles or responsibilities.

The Formalities of Creating a Limited Partnership

Forming a Limited Partnership, on the other hand, is a very deliberate and formal process that demands strict compliance with state law. You create this structure intentionally through legal filings, which establish its crucial liability protections right from the start. You can't just skip these steps—if you fail to comply, the law might not recognize your entity as an LP, potentially exposing your investors to the exact unlimited liability you were trying to avoid.

The formation process involves a few key, non-negotiable steps:

- Draft a Comprehensive Partnership Agreement: This document is the legal cornerstone of your syndication. A well-written LP agreement will meticulously define the roles of the General Partner and Limited Partners, spell out the distribution waterfall, clarify voting rights, and set the terms for the entire deal.

- File a Certificate of Limited Partnership: This official document must be filed with the secretary of state where you choose to form the entity. This filing formally registers the business, names the partners, and serves as a public notice that the limited partners' liability is, in fact, limited.

- Appoint a Registered Agent: Every LP has to designate a registered agent. This can be a person or a service responsible for receiving official legal documents and government mail on behalf of the partnership.

Why Formal Compliance is Crucial for Protection

It's these "formalities" that give the Limited Partnership its power. They create a clear legal record that insulates your passive investors, giving them the confidence they need to put their capital into your deal. As you weigh your options, it's helpful to understand the wider legal context for business entities, like the framework detailed in the UAE Commercial Companies Law.

Beyond the initial setup, you have to stay on top of ongoing compliance to maintain the LP's liability shield. This typically means filing annual reports with the state and paying any required franchise taxes.

Dropping the ball on ongoing compliance, like forgetting to file an annual report, can lead to the state dissolving your LP. That simple administrative mistake could completely strip away the liability protections, putting your investors’ personal assets on the line.

Ultimately, the difference in formation boils down to intent versus informality. A GP can be created by accident, dragging with it accidental and unlimited risks. An LP, however, is built with purpose. Every legal step is designed to protect you, the syndicator, and more importantly, the passive investors whose trust makes the deal possible. This deliberate, compliant approach is the professional standard for any real estate syndicator serious about building a trustworthy, scalable business.

Making the Right Choice for Your Real Estate Deal

When you boil it all down, the choice between a limited and a general partnership becomes pretty clear for a real estate syndicator. This isn't just a box to check on a form; it's a strategic move that shapes how you raise money, protect your investors, and run the show. For nearly every deal that brings in passive investors, the answer is going to be the Limited Partnership (LP) or a similarly structured LLC.

The LP model is practically tailor-made for real estate syndication. It gives investors the one thing they absolutely must have: a liability shield. This ensures their personal assets are safe beyond the capital they put into the deal. That single feature is the foundation of investor trust and makes raising serious capital possible.

Contextual Decision Points

While the LP is the industry standard, there are a few rare situations where another path might make sense. It all comes down to the relationship between the partners and what roles they plan to play.

A General Partnership (GP), for instance, could work for a joint venture between a couple of seasoned developers who are both rolling up their sleeves and managing the project together. In a scenario like that, where everyone is an active participant sharing the same risk and reward, the simplicity of a GP might be fine. But the second you decide to bring in money from outside, passive investors, the GP becomes a non-starter because of its unlimited liability.

As a syndicator, ask yourself one simple question: Am I raising capital from people who won't be involved in managing the property? If the answer is yes, a Limited Partnership is the only structure that correctly matches liability to participation.

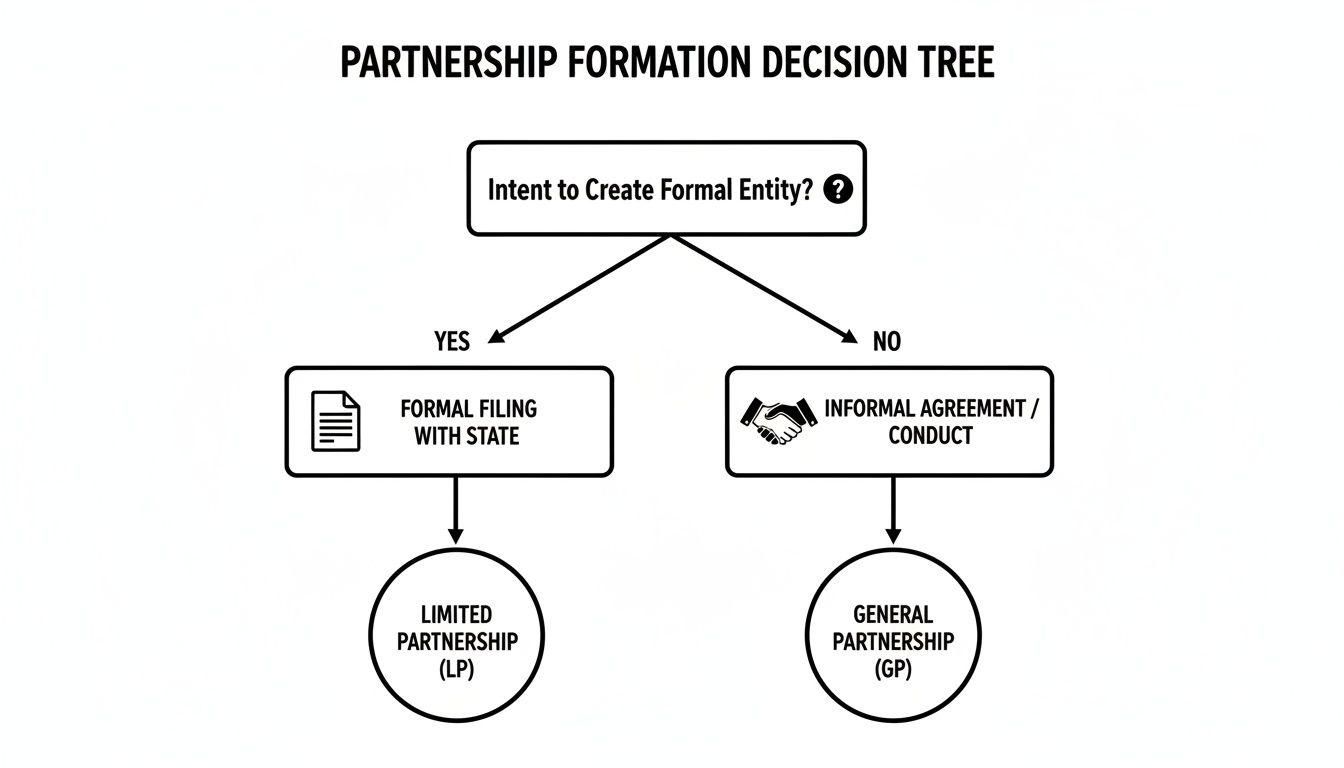

This decision tree gives you a quick visual on how these partnerships come to be, based on how formal you need to be.

As the chart shows, an LP is a deliberate, formal entity created through state filings that provide real legal protections. A GP can be formed almost by accident, leaving partners wide open to risks they never intended to take.

Final Checklist for Syndicators

Before you structure your next deal, run through these questions. If you find yourself nodding "yes" to them, the LP is your best bet.

- Am I raising capital from passive investors? This is the big one. If you are, their protection is everything.

- Do my investors require limited personal liability? Passive investors won't sign a check unless their risk is capped at the amount they invest.

- Do I need sole management control to execute the business plan? An LP puts the decision-making power squarely in your hands as the General Partner.

- Is scalability important for future deals? The LP framework is built to handle a growing number of investors smoothly and efficiently.

For a real estate syndicator, the difference between a limited and general partnership is the difference between a professional, scalable business and a high-risk venture that’s dead on arrival. The LP provides the legal bedrock you need to build a successful syndication company and create lasting relationships with your investors.

Frequently Asked Questions

When you're structuring a real estate deal, the details matter. Getting the partnership right is one of those critical details. Let's tackle some of the most common questions syndicators have when weighing a General vs. a Limited Partnership.

What is the single biggest difference between a general and limited partnership?

It all comes down to liability. Think of it this way: in a General Partnership (GP), every partner is on the hook for everything. Their personal assets are exposed if the deal goes south. A Limited Partnership (LP) builds a firewall for the passive investors (the limited partners). Their risk is capped at whatever amount they invest, while the general partner takes on the unlimited liability.

Can a limited partner participate in managing the property?

Absolutely not. This is a bright, uncrossable line in the sand. A limited partner's role is to be a passive capital provider. The moment they start getting involved in daily management decisions, they risk a court reclassifying them as a general partner. If that happens, their limited liability protection vanishes, and their personal assets are suddenly at risk.

The legal separation of roles is the bedrock of an LP's investor protection. A limited partner's primary role is to provide capital, not operational oversight. Any deviation from this can have severe legal and financial consequences for them.

Why would anyone choose a general partnership for real estate?

For a syndication with passive investors, you wouldn't. It's almost never the right choice. But, you might see a GP used in a very specific scenario: a small joint venture between two or three experienced developers who are all actively managing the project together. When everyone is hands-on and sharing the risk and reward equally, the simplicity of a GP can be attractive. Even then, it's still a high-risk structure.

How much does it cost to form a limited partnership?

The cost will vary depending on your state, but you should budget for a few key items. First, there's the state filing fee, which can be anywhere from $100 to over $750. More importantly, you'll need a lawyer to draft a solid partnership agreement. This isn't a place to cut corners—a well-written agreement protects everyone involved and can easily cost several thousand dollars.

Can a limited partnership have more than one general partner?

Yes, and it's quite common, especially when a deal is sponsored by a team instead of a single individual. When you have multiple general partners, the partnership agreement becomes even more critical. It must spell out exactly who is responsible for what and how major decisions will be made to avoid internal conflicts down the road.

Ready to streamline your next deal? Homebase provides an all-in-one platform to manage fundraising, investor relations, and distributions, letting you focus on what matters most—closing deals and building investor trust. Discover how we can simplify your operations by visiting Homebase today.

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

DOMINGO VALADEZ is the co-founder at Homebase and a former product strategy manager at Google.

What To Read Next

A Syndicator's Guide to Commercial Real Estate Valuation

Blog

Master commercial real estate valuation with our syndicator's guide. Learn the income, sales, and cost approaches to build investor confidence.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

© 2026 Homebase. All rights reserved.