Real Estate Syndication Structures: Your Guide to GP/LP, LLC, and JV Models

Real Estate Syndication Structures: Your Guide to GP/LP, LLC, and JV Models

Explore real estate syndication structures and compare GP/LP, LLC, and JV models with practical insights and real-world scenarios to guide your deal.

Domingo Valadez

Dec 19, 2025

Blog

The way you structure a real estate syndication is everything. It’s the legal and financial blueprint that dictates how the deal is owned, who’s in charge, and how everyone gets paid. Whether you opt for a classic GP/LP structure or a more flexible LLC, this framework defines the roles, liabilities, and tax outcomes for you as the sponsor and for the passive investors funding the deal. Getting this right from the start is non-negotiable for a smooth, compliant, and profitable syndication.

Understanding Real Estate Syndication Structures

At its heart, a real estate syndication is just a partnership. You, the sponsor, bring the deal and the expertise to manage it. Your investors bring the bulk of the capital. This arrangement allows you to tackle bigger assets than you could on your own, and it gives investors a shot at deals without the hassle of property management. But make no mistake: the second you take money from passive investors, you're dealing in securities, and that means you have to play by the SEC’s rules.

The legal entity you form is the vessel that holds the entire deal. It’s the "wrapper" for the property and the rulebook for everyone involved. This isn't a one-size-fits-all situation; it's a critical strategic decision driven by the unique characteristics of your deal.

Key Factors Driving Structural Decisions

The right structure for your deal hinges entirely on its specific needs and your long-term goals. Before we dive into the different models, you need to get clear on the variables that will steer your choice.

- Investor Profile: Are you working with a handful of high-net-worth partners you know well, or are you casting a wider net for accredited investors? The answer directly shapes your compliance and governance requirements.

- Deal Complexity: Buying a stabilized apartment building is a world away from a ground-up development project. The structure has to match the complexity.

- Liability Protection: How insulated do you and your investors need to be from things that could go wrong? This is a huge consideration.

- Tax Implications: Different entities offer different tax treatments. The right choice can dramatically improve net returns for you and your partners through pass-through taxation.

- Sponsor Control: How much day-to-day authority do you want or need? The structure dictates how much control you can legally retain.

The rookie mistake I see all the time is a sponsor defaulting to a familiar structure without really thinking it through. Just because an LLC worked for your last simple multifamily deal doesn't mean it's the right fit for a complex, value-add retail project.

Comparing Common Syndication Frameworks

To get a feel for the landscape, let's look at how the most common real estate syndication structures stack up at a high level. Each model offers a unique mix of flexibility, liability protection, and sponsor control. While we'll get into the nitty-gritty of each one, this table provides a quick side-by-side comparison.

The Classic General Partner and Limited Partner Model

The General Partner/Limited Partner (GP/LP) model is the old faithful of real estate syndication. It’s been the foundation for countless deals for one simple reason: it creates a crystal-clear division of labor. This structure legally separates the active manager from the passive investors, establishing a clean hierarchy for who's in charge and who's along for the ride.

In this setup, the syndicator or sponsor is the General Partner (GP). Think of the GP as the quarterback of the deal—they find the property, line up the financing, manage the day-to-day, and execute the business plan. They hold all the decision-making power. The flip side? They also take on unlimited liability, meaning their personal assets are on the line if things go south.

On the other side of the table, you have the investors, or Limited Partners (LPs). Their role is purely financial. They put up the capital in exchange for equity but have zero management responsibilities or day-to-day control. In exchange for staying passive, their liability is capped at the amount of their investment.

Aligning Interests Through Fees and Waterfalls

So how do you make sure everyone is pulling in the same direction? It all comes down to the financial mechanics, specifically the distribution waterfall. This is a tiered system that spells out exactly how cash flow and profits are paid out, ensuring investors get their money back first before the sponsor gets a major payday.

Here’s how a typical waterfall flows:

- Return of Capital: First and foremost, all LPs get 100% of their initial investment back.

- Preferred Return ("Pref"): Next, investors earn a "pref," which is a fixed annual return (often in the 6%–8% range) on their capital. This is a priority payment; the GP doesn't share in the profits until this hurdle is cleared.

- Catch-Up Clause: Some deals include a catch-up, allowing the GP to take a larger slice of profits for a period until they’ve “caught up” to a specific split.

- Promote/Carried Interest: Once the pref is paid, the remaining profits are split according to a pre-agreed ratio, like 80/20 or 70/30, with the LPs getting the larger share. The GP's portion is called the promote or carried interest—this is their reward for performance.

This waterfall structure is the bedrock of trust in a syndication. It gives investors confidence that their capital is protected while giving the GP a powerful incentive to hit the return targets and earn that promote. It creates a true win-win dynamic.

How Return Hurdles Shape the Deal

Sponsors are getting more sophisticated in how they structure these waterfalls. It’s common to see target internal rates of return (IRR) of 12%–16% for moderate-risk deals. These targets are often baked directly into the waterfall, with the GP's promote "stepping up" at different IRR hurdles. For example, the GP might earn a 20% promote above a 12% IRR, but that could jump to 30% if they deliver an 18% IRR, strongly aligning everyone’s interests to maximize returns.

The Go-To Choice for Traditional Syndications

The GP/LP model is still the best fit for deals with a clear line between an experienced operator and a group of passive financial partners. The governance is refreshingly simple: everyone knows who's driving the bus, which helps avoid conflicts down the road. If you want to dive deeper into the nitty-gritty of this setup, check out our detailed guide on the GP/LP structure.

Because you're raising capital from passive investors, you're dealing with securities law. This means sponsors have to comply with SEC regulations, typically using an exemption like Regulation D, which demands proper documentation and disclosures. The clear-cut roles in the GP/LP model make proving compliance a much more straightforward process.

Comparing The Most Common Syndication Models

While the classic General Partner/Limited Partner (GP/LP) model laid the groundwork for syndication, the modern real estate landscape demands more flexibility and better protection. This is where structures like the Limited Liability Company (LLC) have really taken over, alongside more specialized vehicles like Joint Ventures (JVs) and Delaware Statutory Trusts (DSTs).

Choosing the right structure isn't just a legal formality. It fundamentally shapes how you raise capital, who you partner with, how decisions are made, and how everyone gets paid. Let's break down how these different models work in the real world.

Limited Liability Company (LLC): The Modern Workhorse

There’s a good reason the LLC has become the go-to entity for most real estate syndications. It masterfully blends the tax advantages of a partnership with the robust liability shield of a corporation, giving sponsors and investors the best of both worlds.

The biggest leap forward from the old GP/LP model is liability. In an LLC, everyone is protected, including the sponsor. The sponsor’s personal assets are shielded from the company’s debts, which is a massive relief when you’re tackling a heavy value-add or ground-up development project with significant risk.

Syndications are almost always set up as manager-managed LLCs. This structure neatly mirrors the sponsor-investor dynamic: the sponsor acts as the "manager" with full control over day-to-day operations, while investors are passive "members" with limited voting rights.

The real power of the LLC lies in its operating agreement. This document is a blank canvas, allowing you to customize everything from voting rights and distribution waterfalls to capital call provisions and exit strategies with incredible precision.

Joint Venture (JV): The Strategic Alliance

A Joint Venture is a different beast altogether. You don't typically use a JV to raise money from a crowd of passive investors. Instead, a JV is a strategic partnership between two (or maybe a few) sophisticated groups who are both bringing something more than just cash to the deal. Think of it as a collaboration of equals.

For example, an experienced local developer who has a project fully entitled might partner with an institutional capital provider, like a private equity fund. The developer brings the boots-on-the-ground expertise, and the fund brings the financial firepower. They form a JV to execute the project together, sharing control and profits.

In a JV, everything—management duties, profit splits, decision-making authority—is spelled out in a heavily negotiated JV agreement. There are no passive roles here; both parties are at the table, actively steering the ship.

Delaware Statutory Trust (DST): The 1031 Exchange Solution

The Delaware Statutory Trust, or DST, exists to serve a very specific and powerful purpose: facilitating 1031 exchanges. A 1031 exchange allows an investor to defer paying capital gains taxes on a sold property by reinvesting the proceeds into a "like-kind" property.

The IRS has ruled that an interest in a DST qualifies as a like-kind replacement property. This makes it the perfect passive solution for investors who want to complete their exchange without the headache of finding, acquiring, and managing another property themselves. Sponsors package large, institutional-grade assets into a DST, and multiple 1031 investors can buy fractional interests.

But this structure comes with very strict rules, often called the "seven deadly sins" of DSTs. The sponsor (as trustee) can’t raise new capital once the offering is closed, renegotiate leases with existing tenants, or make major unplanned capital improvements. This rigidity means DSTs are only suitable for stable, long-term assets with predictable cash flow, like a building with a single triple-net lease to a credit-worthy tenant.

At-a-Glance Comparison of Syndication Structures

To help you visualize how these structures stack up, the table below provides a clear, side-by-side comparison. This outlines the key differences between common real estate syndication structures, helping sponsors and investors evaluate the best fit for their specific needs.

Ultimately, the best structure is the one that aligns with your deal’s specific risk profile, your investors’ needs, and your long-term business plan. Each one is a tool, and the key is knowing which one to use for the job at hand.

Exploring Advanced Capital Stack Structures

Seasoned sponsors know that a deal's success often hinges on more than just the primary legal entity. Mastering the entire capital stack—from senior debt to common equity—is what separates the pros. This means getting comfortable with sophisticated financial tools that build flexibility and resilience into your real estate syndication structures.

Two of the most powerful instruments in the toolbox are preferred equity and mezzanine debt. Think of them as hybrid layers you can strategically place between senior bank debt and your common equity investors. They're not just jargon; they're creative solutions for bridging funding gaps, protecting your investors' upside, and attracting capital from different types of sources.

Preferred Equity for Strategic Flexibility

Preferred equity is an incredibly versatile tool that sits above common equity but below all debt in the capital stack. This is a crucial distinction: investors who put in "pref" money get paid before common equity investors see a dime. It's a more secure position.

This structure is perfect for closing that last little funding gap without giving away more of the deal's profit to common equity partners.

- Fixed Returns: Preferred equity investors aren't swinging for the fences. They're looking for a steady, fixed rate of return, usually somewhere between 8% and 12%.

- No Ownership Dilution: Since it's not common equity, bringing in a pref partner doesn't shrink the ownership pie for your original investors.

- Priority Repayment: They get their capital back, plus their promised return, before any common equity holders get profit distributions.

Let's say you're $1 million short on a $10 million acquisition. Instead of giving away another 10% of the deal's future profits to new common equity partners, you bring in a preferred equity investor. They get their fixed 10% return, and your original LPs keep their full share of the potentially massive upside from the project.

Mezzanine Debt for Added Leverage

Mezzanine debt, or "mezz," is another hybrid tool, but it acts more like a loan that’s subordinate to the primary mortgage. It’s essentially a second-tier loan, but instead of being secured by the property itself, it’s secured by the ownership interests in the company that owns the property.

Sponsors typically use mezzanine debt to crank up the leverage on a project, especially for value-add or development deals where the senior lender won't fund the entire amount needed. This can juice the overall returns for your equity investors by lowering the amount of cash they have to bring to the table. For deals that need even more specialized capital, sponsors might explore private lending options to round out the capital stack.

Comparing Preferred Equity and Mezzanine Debt

While both instruments can fill gaps in the capital stack, they work very differently and have unique implications for the deal.

So, which one do you choose? It really comes down to your goals and, just as importantly, what the senior lender will allow. Some banks absolutely forbid any secondary debt (like a mezzanine loan), which makes preferred equity your only option.

The game is always changing. We're seeing new twists on these classic models, with the tokenized and fractionalized real estate markets—which hit an estimated $13.7 billion in 2024—pushing sponsors to include digital-security language in their documents to give investors more liquidity. At the same time, GPs with deep operational expertise now manage about 37% of real estate AUM, leading to structures that heavily feature performance-based promotes and active management fees. You can dive into more insights about these syndication trends and their economic impact.

How To Choose The Right Structure For Your Deal

Picking the right framework for a real estate syndication isn't about finding a one-size-fits-all "best" option. It's about matching the structure to the specific DNA of your deal. The right choice synchronizes your legal and financial setup with your asset strategy, investor profile, and tolerance for risk. This decision demands a methodical approach, not just defaulting to whatever you did last time.

The first step is to diagnose your deal by asking a few critical questions. The answers will naturally point you toward the most logical structure, whether that’s a flexible LLC for a complicated repositioning or a straightforward GP/LP model for a simple acquisition.

Key Questions To Guide Your Decision

Before you even think about drafting documents, run through this mental checklist. It will bring a ton of clarity to your operational needs.

- What's the deal's risk profile? A high-risk, value-add development project screams for the robust liability protection an LLC provides for everyone involved. On the flip side, a stabilized, cash-flowing building with a long-term tenant could fit perfectly into a more traditional GP/LP structure.

- Who are your investors? Are you teaming up with a few sophisticated, hands-on partners in a Joint Venture? Or are you raising capital from a wider pool of passive, accredited investors? That second group absolutely requires the formal protections and clear lines of authority found in an LLC or GP/LP model.

- How much control do you need? If you need absolute day-to-day control to pull off a complex business plan, a manager-managed LLC or a GP/LP structure is essential. A JV, by its very nature, means you're sharing the driver's seat.

- What’s the long-term play? If your primary goal is to create a vehicle for 1031 exchange investors, a Delaware Statutory Trust (DST) is really your only option, even with its operational inflexibility.

The structure you choose sends a clear signal to potential investors. A well-chosen LLC for a development project communicates foresight and protection, while forcing a deal into the wrong structure can raise red flags about a sponsor's experience.

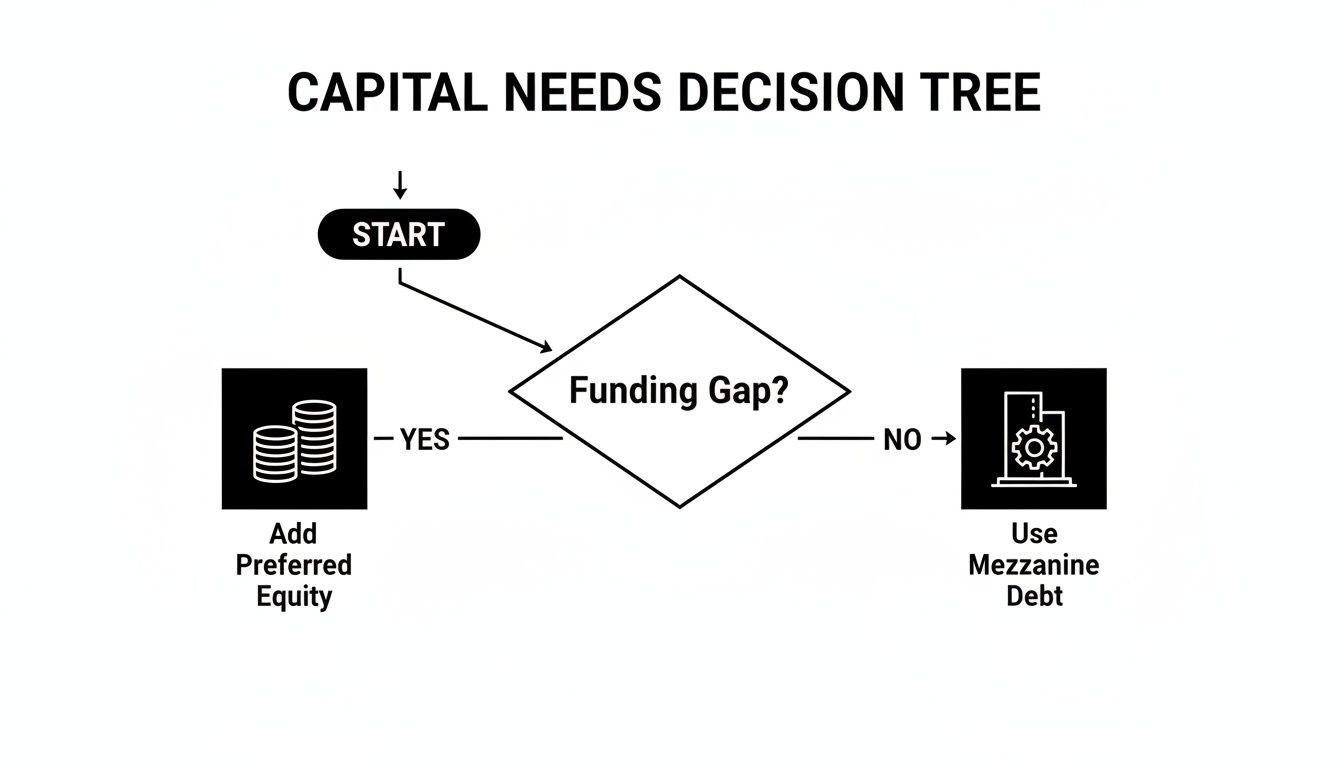

This decision tree shows how your capital needs can influence choices deeper in your capital stack, like when to bring in preferred equity or mezzanine debt.

As the graphic shows, when there's a funding gap, preferred equity is often the go-to solution to avoid diluting the common equity partners.

Applying This Framework to Real-World Scenarios

Let's walk through two different deals. Imagine a sponsor is buying a stabilized multifamily property in a strong market. They might opt for a simple GP/LP structure because the asset's resilience and predictable cash flow lower the perceived risk for everyone. Multifamily has a stellar track record; in 2023, rental rate growth hit 7.1% in some markets, and the entire asset class saw a loan delinquency rate of a mere 0.4% during the 2008 crisis. That kind of history justifies a structure with clear, traditional lines of authority and liability.

Now, picture a sponsor taking on a ground-up construction project. They should almost certainly use an LLC. The built-in risks of development—construction delays, budget overruns, and lease-up uncertainty—make the universal liability shield of an LLC completely non-negotiable for both the sponsor and the investors.

Once you’ve settled on a model, using essential legal templates for your various agreements can save a ton of time and help ensure you're buttoned up. Ultimately, by systematically checking your deal against these core questions, you can confidently select the real estate syndication structure that truly sets your project up for success.

Common Questions About Syndication Structures

Jumping into the world of real estate syndication can feel like you're learning a whole new language. Even when you think you have a handle on the main structures, a ton of questions pop up once you start digging into the nitty-gritty of a deal. Let's tackle some of the most common points of confusion to give you clear, straightforward answers.

My goal here is to demystify the nuances that often get glossed over. Whether you're wondering about the exact legal paperwork you need, how sponsors actually get paid, or when to use a more complicated structure, these answers should help you move forward with more confidence.

What Is The Difference Between A Syndication And A Fund?

This is easily one of the most frequent questions I hear, and the difference is critical. A syndication is all about a single, specific asset. Investors pool their money to buy one particular property—they know from day one that they're investing in the apartment building on Main Street or that specific retail center.

A real estate fund, on the other hand, is what we call a blind or semi-blind pool of capital. Investors commit their money to the fund manager (the sponsor), who then goes out and acquires multiple properties over a set period. In this case, investors are betting on the sponsor’s strategy and track record, not on a pre-identified asset.

Key Takeaway: Think of it this way: a syndication is a one-to-one investment (your capital goes to one specific property), while a fund is a one-to-many investment (your capital is spread across a portfolio). Syndications let you do deep due diligence on a single asset, whereas funds offer instant diversification.

What Legal Documents Are Essential For A Syndication?

You can't just shake hands on a deal. Setting up a legally sound syndication requires a specific set of documents that protect both you (the sponsor) and your investors. While templates can give you an idea, these documents absolutely must be drafted or reviewed by a qualified securities attorney. No shortcuts here.

The core package you'll need includes:

- Private Placement Memorandum (PPM): This is the bible for your deal. It’s the master disclosure document that lays out everything: the business plan, property details, financial projections, every conceivable risk, and the sponsor’s background.

- Operating Agreement (for an LLC) or Partnership Agreement (for a GP/LP): This is the rulebook for your new company. It governs how everything will run, defining voting rights, distribution waterfalls, who has management authority, and how you’ll eventually exit the deal.

- Subscription Agreement: This is the official contract between an investor and your syndication. The investor fills this out to formally subscribe to the offering, state how much they're investing, and confirm their accreditation status.

These three documents are the pillars of a compliant and transparent investment.

How Does The Sponsor (GP) Make Money?

Sponsors don't work for free. They're compensated for the immense effort it takes to find a deal, manage it, and execute the business plan. This compensation is usually a mix of fees for specific work and a larger, performance-based incentive tied to the deal's success.

Here’s a typical breakdown of how sponsors get paid:

This structure ensures the sponsor is paid for their upfront work while heavily motivating them to hit it out of the park for investors to earn that larger profit share.

Can I Advertise My Syndication Deal?

This is a huge question, and the answer depends entirely on the SEC exemption you use. Under Regulation D, syndicators almost always rely on one of two options.

- Rule 506(b): This is the old-school, most common route. With this one, you cannot publicly advertise or generally solicit. You can only raise capital from investors with whom you have a pre-existing, substantive relationship. The upside? You can accept up to 35 non-accredited (but "sophisticated") investors.

- Rule 506(c): This exemption allows you to publicly advertise your deal—shout it from the rooftops on social media, in newsletters, or at conferences. The catch is that you can only accept accredited investors, and you have to take reasonable steps to actually verify that they are accredited.

Choosing the right exemption is a major strategic decision. Rule 506(b) is perfect for sponsors with a solid existing network, while Rule 506(c) is designed for those who need to cast a wider net to find new investors.

Managing the complexities of any of these real estate syndication structures—from fundraising and documentation to distributions and investor communication—can be a huge lift. Homebase provides an all-in-one platform designed to automate the busywork, letting you focus on finding great deals and building investor relationships. Learn how you can streamline your entire syndication process by visiting the Homebase website.

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

DOMINGO VALADEZ is the co-founder at Homebase and a former product strategy manager at Google.

What To Read Next

Definition of Repositioning: definition of repositioning in investing

Blog

Learn the definition of repositioning in multifamily real estate with practical strategies, models, and risk insights to boost profits.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

© 2026 Homebase. All rights reserved.