The GP LP Structure Explained for Real Estate Investors

The GP LP Structure Explained for Real Estate Investors

Unlock real estate syndication with this guide to the GP LP structure. Learn the roles, economics, and legal frameworks that power successful property deals.

Domingo Valadez

Dec 14, 2025

Blog

At its core, the gp lp structure is a powerful partnership model. It brings together a real estate expert who finds and manages the deal (the General Partner or GP) and the investors who provide most of the cash (the Limited Partners or LPs). This framework is the backbone of almost every real estate syndication, letting skilled operators take down large, complex projects using capital from passive investors.

Think of it as a strategic alliance built on a very clear division of labor and risk.

The Engine of Real Estate Syndication

A great way to visualize this structure is to think about a movie production. The General Partner is the director. They are in charge of everything from start to finish—scouting the location (finding the property), lining up the financing, hiring the crew (property managers, contractors), and executing the creative vision (the business plan). They live and breathe the project every single day.

The Limited Partners are the studio financiers. They write the checks that get the movie made, but you won't find them on set adjusting cameras or directing actors. Their role is absolutely critical but intentionally passive. They're betting on the director's expertise to deliver a blockbuster, and for that, they expect a significant share of the profits.

Defining the Core Partnership

This model is the standard in private equity real estate for a simple reason: it solves a classic problem. An experienced sponsor might have the skills to find a great deal and execute a business plan but lacks the millions in equity needed to close. Meanwhile, many investors have the capital but not the time, expertise, or desire to manage a commercial property themselves. The GP/LP structure elegantly bridges that gap.

This partnership is designed to align incentives. The GP's major payday, known as "carried interest," typically only occurs after the LPs have received their initial investment back plus a predetermined preferred return. This ensures the director only wins big if the studio financiers win first.

The whole arrangement is formalized through a legal entity, most often a Limited Liability Company (LLC) or a Limited Partnership (LP). This legal wrapper is crucial because it provides important protections and clearly defines the rules of the game for everyone involved.

For a clearer picture, let's break down the roles.

GP vs LP Roles at a Glance

This table offers a quick comparison of who does what in a typical deal.

Understanding this division of labor is the first step to grasping how these complex deals come together.

A few key benefits really stand out:

- Access to Larger Deals: By pooling their money, LPs can get a piece of institutional-quality assets they could never afford on their own.

- Defined Roles and Responsibilities: The GP does the heavy lifting, allowing LPs to invest passively without getting bogged down in operations.

- Limited Liability for Investors: This is a huge one. An LP’s risk is strictly confined to their investment, protecting their other assets if the deal goes south.

To see how this model fits into the wider world of business, it’s helpful to understand the different ways people structure commercial ventures. This overview on exploring business structures in Australia provides good context. While laws differ by location, the core ideas of allocating risk, responsibility, and reward are universal. This foundation helps explain why the GP/LP framework has become the go-to for collaborative real estate investing.

The Two Sides of the Partnership Coin

At its core, a successful gp lp structure is built on a very intentional division of labor. Think of it as a strategic partnership: one side brings the expertise and does the heavy lifting, while the other provides the capital to make it all happen.

Each side of this partnership has distinct, crucial responsibilities. The General Partner is the operator, the one with boots on the ground. The Limited Partners are the investors who provide the financial fuel. Getting this dynamic right is everything, so let's break down what each role really entails.

The General Partner: The Active Architect

The General Partner (GP) is the engine of the entire deal. This is an all-in role that requires serious real estate know-how, a massive time commitment, and a stomach for risk. The GP is the one who finds the deal, puts it together, and executes the business plan.

Long before an investor ever sees a pitch deck, the GP is hard at work. Their responsibilities include:

- Sourcing and Underwriting: The GP is constantly hunting for properties that fit the investment strategy. This means sifting through dozens, sometimes hundreds, of potential deals, running the numbers, and stress-testing financial models to find that one golden opportunity.

- Due Diligence and Negotiation: Once they’ve locked onto a target, the GP spearheads the exhaustive due diligence process. We’re talking physical inspections, environmental surveys, legal reviews, and lease audits—all while hammering out the purchase price and contract terms with the seller.

- Securing Financing: The GP is also responsible for lining up the loan. This isn't just a matter of filling out paperwork; it often means personally guaranteeing millions of dollars in debt, putting their own assets on the line.

This personal guarantee is a huge deal. It’s a level of personal financial risk that LPs are completely shielded from, and it’s one of the clearest signals of the GP's commitment to the project.

Once the deal is closed, the GP’s job shifts to execution—managing the property day-to-day, overseeing renovations, and handling all the investor reporting until the asset is eventually sold. They are compensated for this "sweat equity" and their ability to generate returns. To learn more, our guide provides a complete general partner definition and a closer look at their wide-ranging responsibilities.

The Limited Partner: The Passive Capital Engine

The Limited Partner (LP) role is the complete opposite—it’s intentionally passive and purely financial. LPs are often busy professionals, like doctors, lawyers, or tech executives, who want the benefits of real estate investment without the headaches of being a landlord. Their essential contribution is the capital that gets the deal off the ground.

An LP's involvement is front-loaded. Their job is to:

- Evaluate the Opportunity: An LP’s main task is to vet the deal presented by the GP. This means scrutinizing the sponsor's track record, the property itself, and the proposed business plan.

- Commit Capital: If they like what they see, they sign the legal documents (like a subscription agreement) and wire their funds to commit to the project.

- Stay Informed: From that point on, their role is simply to receive and review the performance reports and updates sent by the GP.

The single most important aspect of being an LP is limited liability. This is a legal shield that ensures an LP's risk is capped at the exact amount of their investment. No matter what happens—a lawsuit, a loan default—their personal assets are protected. This structure is what allows them to access large-scale real estate opportunities with a clearly defined and manageable risk.

Following the Money Through the Waterfall

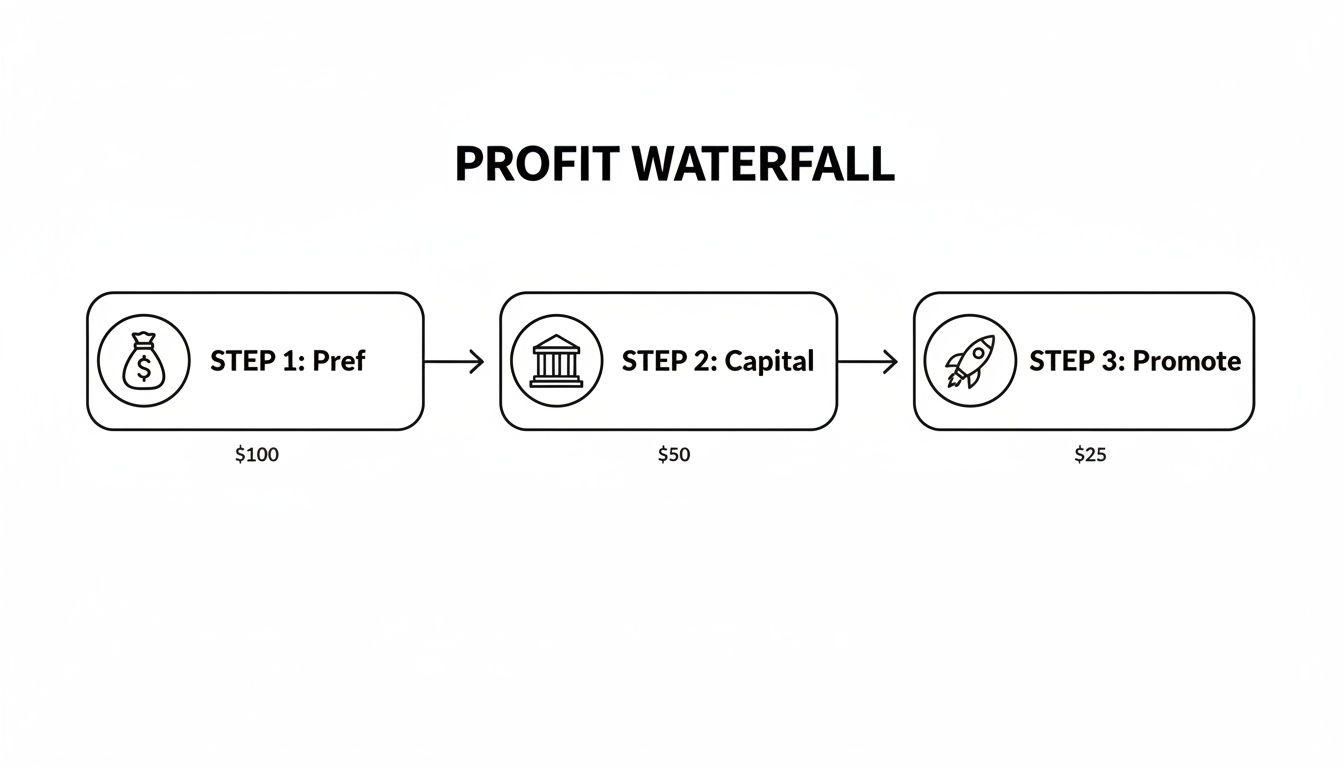

In any investment, you absolutely have to know how the money flows. In a real estate syndication, that flow follows a very specific, tiered system called the distribution waterfall. The best way to picture it is a series of buckets, one spilling over into the next. The second bucket can’t get a drop until the first one is completely full, and so on.

This whole setup is designed to make sure everyone's interests—the General Partner's and the Limited Partners'—are pulling in the same direction. It gives the GP a powerful reason to knock it out of the park, because their biggest payday only arrives after the investors have hit their own return targets. Let’s walk through how this financial engine actually works, piece by piece.

The GP's Compensation for Day-to-Day Operations

Before we even talk about profits, we have to acknowledge the immense amount of work the General Partner does to manage the deal. For all that effort, they’re typically paid fees, which are treated as regular operational expenses of the project.

These aren't profit splits; they're compensation for the job. Here are the most common ones you'll see:

- Acquisition Fee: A one-time fee for finding, underwriting, and closing the deal. This is usually 1-2% of the purchase price and is paid to the GP at closing.

- Asset Management Fee: An ongoing fee for the actual work of running the property—executing the business plan, managing the property manager, and handling investor communications. It's often 1-2% annually, calculated on either the total invested equity or the property's gross income.

- Disposition Fee: When the property is eventually sold, the GP gets a fee for managing that complex process. This is typically 1-2% of the final sale price.

These fees are what keep the lights on for the sponsor's business, allowing them to dedicate their time to making the investment a success long before any profits are realized.

The First Bucket to Fill: The Preferred Return

Once the property starts generating cash flow or is sold, the waterfall officially begins to flow. The very first people in line to get paid are the Limited Partners. This first tier of profit is called the preferred return, or just the "pref."

The preferred return is a critical concept for LPs. It establishes a minimum return threshold, commonly 6-8% per year, that investors must receive on their capital before the GP can start sharing in the profits. Think of it as the GP saying, "You get the first slice of the pie, and only after you've gotten your share do I get mine."

The preferred return is the bedrock of the GP/LP alignment. It forces the GP to clear a performance hurdle before they can earn their big bonus, ensuring they're laser-focused on hitting the LPs' base return expectations first.

It's crucial to understand that a "pref" isn't a guarantee. If the property doesn't generate enough cash to pay it in a given year, the unpaid portion usually accrues (like interest) and gets paid out from future cash flow or sale proceeds before the waterfall can move to the next tier.

The GP's Performance Bonus: Carried Interest

The GP only gets to share in the deal's profits after two major milestones are hit: 1) the LPs have received 100% of their original capital back, and 2) the LPs have been paid their full, cumulative preferred return. That performance-based bonus for the GP is known as carried interest, or the "promote."

This is the GP’s reward for a job well done. The promote is their disproportionate share of the profits, and it's what truly motivates them to outperform. If a GP puts in 5% of the equity, they don't just get 5% of the profits; their carried interest might give them 20% or 30% of the profits after the LPs have been made whole and received their pref. This is where the gp lp structure really shines—the GP's biggest reward is directly tied to creating exceptional returns for their investors.

In this model, a sponsor's compensation has two parts. They earn ongoing management fees, which typically average around 2% of committed capital (ranging from 1.1% to 5%), and they earn carried interest. Carried interest is most commonly 20% of the profits after the LPs get their capital back plus an 8% preferred return. On a $100 million fund, a 2% management fee alone provides the GP with $2 million annually to run their operations. For a deeper dive into this compensation model, you can check out this overview of limited partnerships.

A Simplified Waterfall Example

Let’s tie it all together with a quick, practical example of how the money flows.

- Return of Capital: First, 100% of the initial investment is returned to the LPs. If a group of investors put in $1 million, they are the first to get that $1 million back from cash flow or a sale.

- Preferred Return: Next, the LPs receive their pref. With an 8% pref on that $1 million investment, they will continue to receive all distributable cash until they've hit that 8% annual return hurdle.

- The Promote Split: Only after those first two buckets are full are the remaining profits split. A very common split is 80/20—80% of the remaining profit goes to the LPs, and 20% goes to the GP as their carried interest.

This structure creates a logical, fair, and transparent path for the money, prioritizing the investors who funded the deal while handsomely rewarding the sponsor for delivering great results.

The Legal Blueprint of the Partnership

While it's great to understand the roles and profit splits in theory, none of it means anything until it's down on paper. This is where the legal framework comes in—it’s the actual blueprint for the investment, meticulously drafted to protect both the General Partner (GP) and the Limited Partners (LPs).

Think of these documents as the official rulebook for the game. They take the deal from a handshake to an ironclad contract, spelling out every responsibility, every fee, and exactly how every dollar of profit gets distributed. For any serious investor, digging into this legal architecture isn't just a suggestion; it's an absolute must.

The Rulebook for the Entire Deal

The absolute cornerstone of the GP/LP structure is the Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA). If the deal is structured as an LLC, you'll hear it called the Operating Agreement. Same concept, different name. This is, without a doubt, the single most important document you'll encounter.

This agreement governs the entire relationship between the sponsor and their investors from day one until the final check is cut. It's often dense and packed with legalese, but hidden within are the critical details that define the partnership:

- Partner Roles and Responsibilities: It clearly outlines what the GP is authorized to do—manage the property, sign for a loan, execute the business plan—and confirms the LPs' role is strictly as passive capital providers.

- Voting Rights: LPs aren't running the show, but they usually get a say on huge decisions. The LPA specifies what requires an LP vote, like selling the property or refinancing, and what percentage of votes is needed for approval.

- Distribution Waterfall Mechanics: This is where the money is. The LPA details the exact sequence and percentages for all distributions, from the return of capital and preferred return to the GP's performance-based promote.

The Limited Partnership Agreement is where the sponsor's financial model becomes legally binding. It's the ultimate source of truth for how and when money flows, making it essential reading for any prospective LP.

A well-crafted LPA doesn't leave anything up for debate. It's a clear roadmap for handling just about any situation that could arise, ensuring everyone is held to the exact terms they agreed to from the start.

The profit waterfall is a core piece of this agreement, mapping out how cash flows from the property back to the partners.

This visual breaks down the sequence perfectly. First, the LPs get their preferred return, then they get their initial capital back, and only then does the sponsor start earning their promote. It's a crystal-clear illustration of how investors are put first before the GP gets their performance bonus.

The Investor's Official Commitment

So, if the LPA is the rulebook for the whole partnership, how does an individual investor actually join? That's what the Subscription Agreement is for. This is the document you sign to officially get in on the deal.

Signing the sub doc is your formal application to become a partner and commit your capital. It’s the moment you "subscribe" to the investment, legally binding yourself to the terms laid out in the LPA.

This document typically covers three key things:

- Capital Commitment: You'll state the exact dollar amount you are investing in the project. This is your official pledge.

- Accreditation Status: You have to confirm that you meet the SEC's definition of an accredited investor, which is a requirement for most private real estate deals.

- Acknowledgement of Risk: This section confirms that you've received and reviewed all the deal documents (especially the LPA) and that you fully understand the risks involved.

Once you sign and the GP countersigns your subscription agreement, you're officially a Limited Partner. It’s that simple. Together, the LPA and the Subscription Agreement create a complete legal shield that ensures the partnership runs with clarity and fairness for everyone. Reading these documents isn’t just a formality—it's the most important piece of due diligence an investor can do.

Liability and Taxes: The Real Power of the GP/LP Structure

Beyond just who does what and who gets paid, the GP/LP structure is the go-to model in real estate for two big reasons: it shields investors from risk and it's incredibly tax-efficient. These aren't just minor perks; they're foundational protections that shape the entire deal. If you're going to invest in or sponsor a syndication, you have to get this part right.

At its core, the structure is designed to create a very deliberate wall between different types of risk. For the passive investors, the Limited Partners, this is arguably the most important feature of the entire setup.

The Investor's Safety Net: Limited Liability

The promise to every LP is simple: limited liability. This is a powerful legal concept that says the absolute most an investor can lose is the money they put into the deal. That’s it. If a major lawsuit hits, an environmental disaster happens, or the loan goes into default, the LPs’ personal assets—their homes, savings, and other investments—are completely off-limits.

This protection is what makes passive investing work. It allows someone to put capital into a multi-million dollar asset without shouldering the catastrophic risk that could come with it. You get the upside of a big project with a clearly defined downside, which is a must-have for almost any passive investor.

How Sponsors Protect Themselves

On the flip side, the General Partner traditionally has unlimited liability. By default, a GP is personally on the hook for every single debt and obligation of the partnership. As you can imagine, very few sponsors are willing to sign up for that kind of exposure. It’s a massive, and unnecessary, risk.

The solution is straightforward. Sponsors almost always form a separate legal entity, typically a Limited Liability Company (LLC), to act as the official "general partner." This simple step walls off the sponsor's personal assets from the deal's liabilities. The risk is now contained within the GP's business, not tied to their personal net worth. It’s a critical and standard piece of the puzzle.

A defining feature of the GP-LP structure is the liability divide: GPs bear unlimited joint and several liability for partnership debts, mirroring conventional partners, while LPs risk only their capital contribution, making it ideal for passive investors in private equity and venture capital. Learn more about how this legal framework protects investors from the Bank for International Settlements.

This strategic use of entities isn’t a loophole; it’s just smart business and the proper way to structure a modern real estate deal.

Why This Structure is a Tax-Lover's Dream

The second huge advantage of the gp lp structure is how it's treated by the IRS. Both Limited Partnerships and LLCs are considered pass-through entities. This is a game-changer compared to the old-school way of investing through a C-corporation.

So, what does "pass-through" actually mean for you?

- The partnership entity itself pays no corporate income tax.

- Instead, all the financial results—the profits, losses, and juicy depreciation deductions—are "passed through" directly to the individual partners.

- The GP and each LP receive a Form K-1 at the end of the year detailing their share, which they then report on their personal tax returns.

This setup brilliantly sidesteps the double taxation problem you see with C-corps, where the company gets taxed on its profits, and then investors get taxed again when they receive dividends. The pass-through model ensures the profits from the property are only taxed once, at the individual's level, which means more money stays in the pockets of the people who invested it.

A Real-World Deal Walkthrough

Theory is great, but nothing makes these concepts sink in like seeing the numbers play out in a real deal. Let's walk through a simplified, hypothetical scenario to show you exactly how the GP/LP partnership works from the initial purchase all the way to a profitable sale. We'll trace every dollar as it flows through a common distribution waterfall.

Imagine a sponsor—our General Partner (GP)—finds a promising apartment complex with a $5 million price tag. After running the numbers, they figure they need $1.5 million in equity to satisfy the lender and cover upfront costs. The other $3.5 million will be financed with a bank loan.

Breaking Down the Capital Stack

The "capital stack" is just a fancy term for where the money to buy the property comes from—in this case, a mix of debt and equity. The GP's immediate job is to raise that $1.5 million equity piece.

Here’s a typical way they might structure the partnership:

- General Partner (GP) Contribution: The GP puts in $150,000 of their own money. This is 10% of the total equity and is crucial for showing they have real "skin in the game."

- Limited Partner (LP) Contribution: The GP then raises the other $1,350,000 from passive investors, who collectively contribute 90% of the equity.

With the funding locked in, the GP closes the deal and gets to work on the business plan. Let's fast-forward three years. The GP's strategy worked perfectly; they've boosted the property's income and just sold it. After paying back the loan and all transaction costs, there's a neat $1,000,000 profit left over.

Following the Money Through the Waterfall

So, how does that $1,000,000 profit get carved up? This is where the waterfall distribution outlined in the partnership agreement comes into play. For this deal, let’s assume a very common structure: an 8% preferred return for the LPs, followed by a 70/30 split of any remaining profit.

Tier 1: Return of Capital

First things first, everyone gets their initial investment back. This is non-negotiable.

* The LPs are returned their $1,350,000.

* The GP is returned their $150,000.

Tier 2: The Preferred Return ("Pref")

Next up, the LPs get paid their preferred return. It’s their reward for putting their capital at risk.

* The agreement promises them 8% per year on their $1,350,000 investment.

* Over three years, this comes out to $324,000 ($108,000 per year).

This $324,000 comes directly out of the $1,000,000 profit pool. We now have $676,000 left to distribute ($1,000,000 - $324,000).

Tier 3: The Carried Interest ("Promote") Split

Now for the final split. This is where the GP gets rewarded for a job well done. The remaining $676,000 is divided based on the 70/30 split.

* LP Share (70%): The LPs get 70% of the remaining profit, which is $473,200.

* GP Share (30% "Promote"): The GP earns the remaining 30%, which amounts to $202,800.

To help visualize this, here’s a table breaking down how that $1M profit is distributed after all capital has been returned.

Sample Waterfall Distribution for a $1M Profit Scenario

When all the dust settles, the LPs have turned their $1,350,000 investment into a total return of $2,147,200 (their initial capital back + their share of the profits). The GP, on the other hand, turned their $150,000 investment into a total return of $352,800 (their capital back + the promote).

This is the beauty of the structure. It aligns incentives by ensuring investors are paid first and generously, while still giving the sponsor a powerful financial motivation to outperform and deliver a home-run deal.

Answering the Tough Questions: The GP/LP Structure in Practice

Even after you've got the basics down, real-world scenarios always bring up more questions. Let's tackle some of the most common ones that both new sponsors and investors ask about the GP/LP structure.

What Happens If a Deal Goes Sideways?

It’s the question no one wants to ask, but everyone needs to know: what if the project loses money?

The answer lies in the legal structure. For Limited Partners (LPs), the pain stops at their initial investment. Thanks to limited liability, they can't lose more than the capital they put in. Their personal assets are completely walled off from the deal's debts.

The General Partner (GP), on the other hand, is on the hook. This is why you almost never see an individual acting as the GP. Instead, sponsors create a separate legal entity, usually an LLC, to serve as the General Partner. This is a critical move that shields their personal net worth from the project’s liabilities.

Can LPs Meddle in Management Decisions?

Simply put, no. And for a very good reason. The "limited" in Limited Partner refers directly to their liability, which is preserved by their passive role.

If an LP starts getting involved in the day-to-day operations—making management decisions, directing contractors, or negotiating leases—they risk losing their protected status. The courts could see them as acting like a General Partner, potentially exposing them to the same unlimited liability.

That said, LPs aren't totally without a voice. A well-drafted partnership agreement will give them voting rights on huge, game-changing decisions, like selling the property or taking on major new debt. This gives them a say in protecting their capital without getting into the operational weeds.

How Does a GP Make Money with So Little Skin in the Game?

It's a common misconception that a GP's contribution is only measured in dollars. In reality, they are paid for their expertise, the sweat equity of finding and managing the deal, and for taking on the lion's share of the risk.

Their compensation is structured to reward performance:

- Fees: Sponsors charge various fees (for acquisition, asset management, etc.) that help keep the lights on and cover the overhead of running the project.

- Carried Interest (Promote): This is the real prize. The "promote" is the GP's outsized share of the profits. But here's the key: they only get this bonus after every single LP has been paid back their entire initial investment, plus a pre-agreed-upon preferred return.

This structure ensures the GP is laser-focused on one thing: making the deal a success for their investors. If the LPs don't win, the GP doesn't get their big payday.

Juggling investor questions, sending out K-1s, and processing distributions can feel like a full-time job. Homebase is a purpose-built platform designed to automate the heavy lifting of real estate syndication. It gives you a single, professional portal to manage fundraising and investor communications, freeing you up to focus on the deals. See how it works and schedule a demo today.

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

DOMINGO VALADEZ is the co-founder at Homebase and a former product strategy manager at Google.

What To Read Next

Definition of Repositioning: definition of repositioning in investing

Blog

Learn the definition of repositioning in multifamily real estate with practical strategies, models, and risk insights to boost profits.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

© 2026 Homebase. All rights reserved.