Mastering the Income Capitalization Approach

Mastering the Income Capitalization Approach

A complete guide to the income capitalization approach. Learn how to calculate property value using NOI, cap rates, and real-world examples.

Domingo Valadez

Aug 5, 2025

Blog

The income capitalization approach is a cornerstone of commercial real estate valuation. At its heart, it’s a method for figuring out what a property is worth based on the income it brings in. Think of it less like buying a house to live in and more like buying a small business—you're primarily interested in its profitability.

A great analogy is buying a fruit tree. You don't just value it for its wood or how nice it looks in the yard. You value it for the fruit it's going to produce, year after year.

The Foundation of Real Estate Investment Value

For a real estate syndicator, a property isn't just bricks and mortar; it's an income-generating machine. The income approach cuts through aesthetic appeal and emotional bias to focus squarely on what matters most to an investor: cash flow. It’s the bedrock of commercial real estate analysis precisely because it ties a property's financial performance directly to its current market value.

Instead of asking, "What did the building next door sell for?" this method forces you to ask, "What is this asset worth based on the money it actually makes?" That shift in perspective is everything when you're making smart investment decisions.

Two Sides of the Same Coin

To really get a grip on the income approach, you need to understand its two key components. They work together to paint a clear financial picture.

- Net Operating Income (NOI): This is the pure, unadulterated profit a property generates before you factor in mortgage payments (debt service) or income taxes. It’s calculated by taking all the property's revenue and subtracting all the necessary operating expenses.

- Capitalization Rate (Cap Rate): This is the expected rate of return on an investment property. The cap rate is a market-driven metric that reflects the perceived risk and potential of a certain property type in a specific area.

When you combine these two figures, you can translate an annual income stream into a single, tangible value.

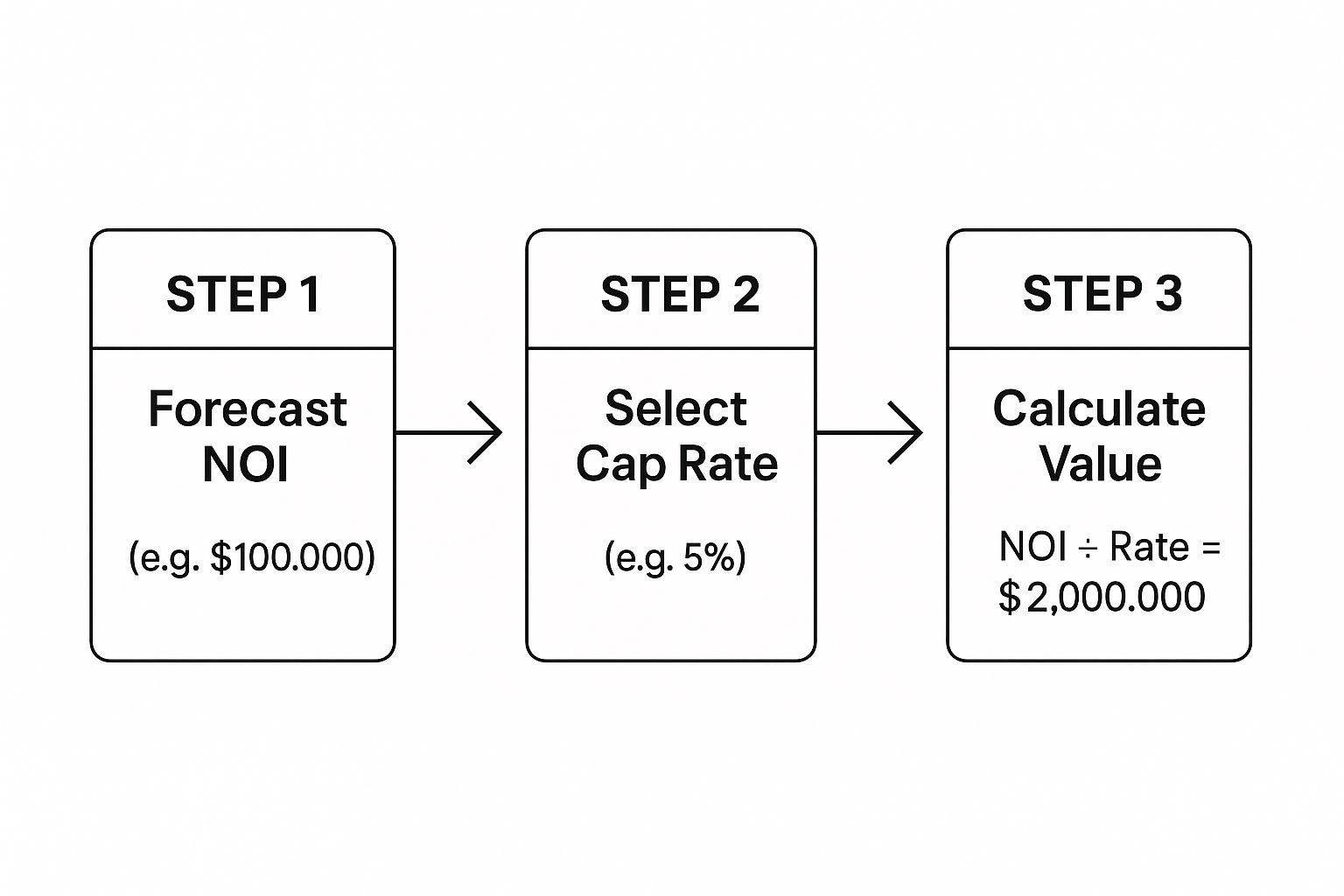

At the end of the day, it all boils down to a simple but powerful formula: Value = Net Operating Income / Capitalization Rate. This is the engine that drives the income capitalization approach, giving you a clear snapshot of a property’s financial worth.

Let's unpack these three elements a bit more.

The Core Components of the Income Approach

To get a feel for how these pieces fit together, here's a quick breakdown of the formula's components and what they represent.

Understanding these roles is key. The NOI is specific to the property, while the Cap Rate is dictated by the market. The Value is the result of their interaction.

How It Works in the Real World

The practical application of this method is refreshingly direct. The income capitalization approach, which is a staple in both real estate and business valuations, converts a single year’s income into a solid estimate of value.

For example, imagine a property generates $182,452 in net operating income. If similar properties in the area have recently sold at a 7.43% cap rate, the math gives you an indicated value of roughly $2,456,000. If you want to dive deeper into the mechanics, you can review this detailed capitalization overview.

This approach is the go-to method for any asset where income is the main driver of value, such as:

- Apartment buildings

- Office complexes

- Retail strip malls

- Industrial warehouses

For syndicators looking at these kinds of deals, the income capitalization approach isn't just another valuation tool—it's a critical piece of the due diligence puzzle.

How to Accurately Calculate Net Operating Income

The Net Operating Income, or NOI, is the absolute heart of the income capitalization approach. It’s the metric that shows you a property's pure, unadulterated profitability before you even think about loans or taxes. Getting this number right isn't just a good idea—it's essential for a valuation you can actually trust.

Think of NOI as the annual profit your property generates all on its own, like a standalone business. Any mistake in this calculation will create a domino effect, throwing off your entire valuation.

Let's walk through it step-by-step, using a small apartment building as our guide.

Step 1: Start with Potential Gross Income

First things first, we need to figure out the Potential Gross Income (PGI). This is your "perfect world" number—the total income the property could possibly earn if it were 100% occupied all year long, with every single tenant paying rent on time and in full.

Let’s say we're looking at a 10-unit building where each apartment rents for $1,500 per month.

- PGI Calculation: 10 units x $1,500/month x 12 months = $180,000 per year.

This number is your revenue ceiling. It's a great starting point, but we all know the real world has other plans. That brings us to our next adjustment.

Step 2: Adjust for Reality to Find Effective Gross Income

No property is full all the time. Life happens. People move out, and sometimes tenants fall behind on rent. You have to account for these realities to get a true sense of your income. This adjustment gives us the Effective Gross Income (EGI), a much more realistic forecast of the cash you'll actually collect.

For our 10-unit building, let's assume a conservative vacancy and credit loss rate of 5%.

- Vacancy & Credit Loss: $180,000 (PGI) x 5% = $9,000

- EGI Calculation: $180,000 (PGI) - $9,000 = $171,000

This $171,000 is your real top-line revenue. It's the money you can reasonably expect to have in the bank to cover all the building's bills. If you want to dig deeper into this, you can learn more about how to find net operating income and see other examples.

Step 3: Deduct All Operating Expenses

The final step to finding your NOI is subtracting all the necessary operating expenses from your EGI. These are the unavoidable costs of keeping the lights on and the property in good shape, whether it’s fully leased or has a few empty units.

An operating expense is any cost that is necessary, ordinary, and directly related to maintaining the property and serving its tenants. If the expense doesn't fit this description, it likely doesn't belong in the NOI calculation.

Common operating expenses you'll see include:

- Property Taxes: The annual bill from the city or county.

- Property Insurance: Coverage for fire, liability, and other potential hazards.

- Utilities: Water, electricity, and gas for common areas (if not billed to tenants).

- Repairs & Maintenance: The day-to-day costs for things like leaky faucets, landscaping, and pest control.

- Property Management Fees: Usually a percentage of collected rent paid to a professional manager.

For our example apartment building, let's say all these costs add up to $60,000 for the year.

Final NOI Calculation: $171,000 (EGI) - $60,000 (Operating Expenses) = $111,000

That $111,000 is your Net Operating Income. It's the key figure you'll use in the income capitalization formula to determine the property's value.

What NOT to Include in Operating Expenses

Knowing what doesn't count as an operating expense is just as crucial. New investors often make the mistake of including costs that don't belong, which can seriously skew the NOI and lead to a bad investment decision.

Be sure to exclude these items:

- Mortgage Payments (Debt Service): Your loan is a financing cost, not an operational one. NOI looks at the property's performance independent of how you paid for it.

- Depreciation: This is a "paper" expense used for tax purposes. It’s an accounting tool, not cash leaving your pocket.

- Capital Expenditures (CapEx): These are major, infrequent upgrades that extend the building’s life—think a new roof, a full HVAC replacement, or repaving the parking lot. They are considered capital investments, not routine expenses.

- Income Taxes: Your personal or business income taxes are tied to you as the owner, not the property itself.

Demystifying The Capitalization Rate

If Net Operating Income (NOI) is the engine that powers a property's value, then the capitalization rate—or cap rate—is the speedometer. It doesn't create the horsepower, but it tells you exactly how fast the market is moving and what kind of performance investors expect. It's often the most debated part of the formula, but it’s really just a simple reflection of market sentiment.

I like to think of the cap rate as a property's financial pulse. It’s a single percentage that measures the delicate balance between the market's hunger for returns and its perception of risk for that specific asset type, in that specific location.

A low cap rate is a signal that a property is considered a safe bet—low risk, high demand, and likely in a prime location. On the flip side, a high cap rate often points to higher perceived risk, weaker growth prospects, or a less desirable market.

How Is The Cap Rate Determined?

Here’s a crucial point: you don't just invent a cap rate. Unlike NOI, which you calculate from a property's unique financial statements, the cap rate is a number you derive directly from the marketplace. The most reliable way to land on a justifiable cap rate is to look at recent, comparable sales (or "comps").

The process is essentially a reverse-engineering of the main valuation formula:

Capitalization Rate = Net Operating Income / Recent Sale Price

By digging into the NOI and sale prices of similar properties that recently traded hands, you can see the rate of return that real-world investors were willing to accept. That market-derived rate then becomes the benchmark you can confidently apply to your target property.

For example, say you find three apartment buildings in the same submarket that recently sold. If their cap rates were 6.1%, 6.3%, and 6.2%, you’d have a very strong case for using a cap rate of around 6.2% to value your property.

Key Factors That Influence Cap Rates

A cap rate is a living number, not a fixed constant. It's incredibly sensitive to a whole range of factors, and as a syndicator, you need to understand what pushes this rate up or down.

The table below breaks down the main drivers. It shows how different market forces and property-specific traits can either compress (lower) or expand (raise) the cap rate, which in turn sways the final valuation.

Key Factors That Influence Cap Rates

As you can see, context is everything. These factors explain why the income capitalization approach is so vital in a market like California, where intense demand in places like Los Angeles and San Francisco leads to lower cap rates. In these robust markets, residential income properties might trade at cap rates in the 4% to 6% range. You can see a real-world analysis of how market conditions affect valuations in California to understand this principle better.

Ultimately, the interplay between these factors is what makes the cap rate such a powerful and nuanced tool.

The Inverse Relationship Between Value And Cap Rate

This is one of the most important—and sometimes counterintuitive—concepts for new investors to grasp. There is an inverse relationship between a property's cap rate and its value.

Let’s break it down with the formula (Value = NOI / Cap Rate):

- A lower cap rate results in a higher property valuation.

- A higher cap rate results in a lower property valuation.

Imagine two identical properties, both generating $100,000 in NOI. Property A is in a booming market and commands a 5% cap rate. Property B is in a slower, less certain market and trades at an 8% cap rate.

Let's do the math:

- Property A Value: $100,000 / 0.05 = $2,000,000

- Property B Value: $100,000 / 0.08 = $1,250,000

Even with the exact same income, the market's perception of risk and growth—all captured in that one little percentage—creates a massive $750,000 difference in value. This is why nailing down the right cap rate isn't just an academic exercise; it's the absolute linchpin of a credible valuation.

When you're digging into the income capitalization approach, you'll find there are two main ways to connect a property's income to its value: Direct Capitalization and Yield Capitalization.

These aren't rival theories; think of them as different tools in your valuation toolkit. Knowing which one to grab depends entirely on the property’s financial story. One method is like taking a sharp, clear photograph of the property’s finances right now. The other is like watching a movie of its financial performance over several years. Both tell you something valuable, but they capture different aspects of the story.

Direct Capitalization: The Financial Snapshot

The method we’ve been exploring so far is Direct Capitalization. It’s the "photograph" approach. You simply take a single year's Net Operating Income (NOI) and divide it by a market cap rate. This gives you a fast, powerful valuation based on the property’s performance at a specific moment—usually the last 12 months or the projected first year of ownership.

So, when does this make sense? It’s perfect for stable, predictable properties. Picture a fully leased office building with solid, credit-worthy tenants locked into long-term leases. The income stream is as steady as a rock, with no major surprises on the horizon.

Direct Capitalization is ideal for: Properties with stable occupancy, predictable cash flows, and minimal upcoming capital projects. It assumes the current NOI is a reasonable proxy for future performance.

The beauty of this method is its simplicity and its direct tie to current market data (i.e., cap rates from comparable sales). The trade-off, however, is that it doesn't explicitly factor in future bumps or dips in income or expenses.

Yield Capitalization: The Financial Motion Picture

But what if the property’s story is a bit more complicated? Maybe you’re planning a big renovation, a few major leases are about to expire, or you're betting on local rental rates taking off. For situations like these, you need the "motion picture" method: Yield Capitalization.

Yield Capitalization, which is almost always done using a Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) analysis, looks far beyond a single year. Instead, you project all the income and expenses over a longer holding period—typically 5 to 10 years. You forecast the cash flow for each year and even estimate the property’s final sale price (its reversion value) when you plan to sell.

Each of those future cash flows, including the big payout from the final sale, is then "discounted" back to what it's worth in today's dollars. This makes it the go-to method for properties with moving parts and less predictable income streams.

An investor would lean on Yield Capitalization for deals like these:

- Value-Add Projects: When planning significant renovations that will disrupt income in the short term but boost it later.

- Lease-Up Properties: For brand-new developments or buildings with high vacancy that need time to fill up and stabilize.

- Irregular Cash Flows: When tenant leases are all over the place, causing income to fluctuate from one year to the next.

At its heart, this technique hinges on the relationship between discount rates, cap rates, and expected growth. For instance, in business valuation, if you project income to grow at a steady 5% a year and your required rate of return (the discount rate) is 25%, the cap rate is simply the discount rate minus the growth rate—a 20% cap rate. This principle, as detailed in this in-depth look at valuation assumptions, helps investors align their long-term growth expectations with a property's present value.

Choosing The Right Method

Picking the right method isn't about which one is better; it's about which one fits the property and your investment plan. An accurate valuation depends on making the right choice.

Ultimately, both are indispensable tools within the income capitalization approach. For a straightforward, stabilized asset, Direct Capitalization gets you a reliable number quickly. But for a complex deal with a multi-year business plan, the detailed, forward-looking analysis of Yield Capitalization is what you need to invest with confidence.

Calculating Property Value Step by Step

Alright, let's roll up our sleeves and move from theory to real-world application. Once you have a firm grip on Net Operating Income (NOI) and the Capitalization Rate, you can put them together to figure out what a property is actually worth. This is where the direct capitalization method truly comes to life, turning a spreadsheet of numbers into a solid valuation.

To make this crystal clear, we'll walk through a detailed, hands-on example. Let's analyze a small retail strip center to see exactly how an investor would calculate its value from the ground up.

Case Study: The Elm Street Retail Center

Imagine you're looking at buying The Elm Street Retail Center. It's a 10,000-square-foot building with four retail units. Our one and only goal right now is to determine its market value using the formula we've been talking about: Value = NOI / Cap Rate.

To get there, we need to knock out three main tasks:

1. Calculate the property's Net Operating Income (NOI) from scratch.

2. Find a realistic Capitalization Rate by digging into local market data.

3. Plug everything into the formula and do a final "gut check" on the result.

Step 1: Gather The Financials And Calculate NOI

First things first, we need the numbers. After getting the rent roll and expense reports from the seller, we can start piecing together our NOI.

A. Calculate Potential Gross Income (PGI)

This is the absolute best-case scenario—the total annual rent if every single unit was occupied and every tenant paid on time.

- Unit 1 (Coffee Shop): $3,000/month

- Unit 2 (Dry Cleaner): $2,800/month

- Unit 3 (Pizza Place): $3,200/month

- Unit 4 (Vacant): Market rent estimated at $2,500/month

- Total Monthly Income: $11,500

- Potential Gross Income (PGI): $11,500 x 12 months = $138,000

B. Find the Effective Gross Income (EGI)

Now, let's get back to reality. We have to account for vacancies and tenants who might not pay. With one unit already empty and considering general market risks, we'll apply a conservative 8% vacancy and credit loss rate.

- Vacancy & Credit Loss: $138,000 x 8% = $11,040

- Effective Gross Income (EGI): $138,000 - $11,040 = $126,960

C. Tally Operating Expenses and Finalize NOI

With our realistic income figure, it's time to subtract all the costs of running the property.

- Property Taxes: $20,000

- Insurance: $5,500

- Common Area Maintenance (CAM): $12,000

- Management Fee (4% of EGI): $5,078

- Total Operating Expenses: $42,578

- Net Operating Income (NOI): $126,960 - $42,578 = $84,382

There it is. Our property generates an annual NOI of $84,382. This is the "I" in our valuation formula.

Step 2: Determine The Market Cap Rate

With our NOI locked in, we need the other half of the equation: the cap rate. This isn't a number you just invent; it’s driven by what's happening in the local market. So, we'll research recent sales of similar small retail centers in the immediate area.

Our digging turns up three comparable sales:

- Comp 1: Sold for $1.2M with a $78,000 NOI. Cap Rate = 6.5%.

- Comp 2: A slightly older property, sold for $950k with a $68,400 NOI. Cap Rate = 7.2%.

- Comp 3: A prime location, sold for $1.5M with a $93,000 NOI. Cap Rate = 6.2%.

This data gives us a clear market range between 6.2% and 7.2%. Considering our property's solid condition but also its existing vacancy, landing somewhere in the middle feels right. Let’s go with a cap rate of 6.75%.

Step 3: Calculate Value And Perform A Sanity Check

We finally have both pieces of the puzzle. Now for the easy part—plugging the numbers into the formula to see what the property is worth.

Value = NOI / Cap Rate

Value = $84,382 / 0.0675

Estimated Value = $1,250,103

Based on our analysis, The Elm Street Retail Center has an indicated value of right around $1,250,000.

This visual here breaks down the entire process, showing how we went from income streams to a final valuation.

As you can see, each step builds on the last. We funnel property-specific data (NOI) and market-wide data (Cap Rate) into a single, defensible number.

But we're not quite done. The last, and arguably most important, step is the sanity check. Does $1.25 million feel right? It sits comfortably within the sales prices of our comps ($950k to $1.5M). It also works out to a price of $125 per square foot, which sounds perfectly reasonable for this kind of building in this market. The math holds up, giving us the confidence we need to proceed.

When you’re evaluating a real estate deal, you need the right tool for the job. The income capitalization approach is a powerhouse, but like any tool, you need to know when—and when not—to use it. Its biggest advantage is that it gets straight to the point, focusing on what every investor really cares about: how much cash a property can actually produce.

This is why it's the undisputed heavyweight champion for valuing commercial, income-generating properties. We're talking about apartment buildings, office towers, shopping centers, and industrial warehouses. For these types of assets, value is directly linked to the rent checks coming in, making the income approach the most logical and relevant way to size them up.

But here’s the catch: its greatest strength is also its biggest potential pitfall. The entire valuation rests on just two critical assumptions: the Net Operating Income (NOI) and the capitalization rate. If you get those wrong, the whole calculation goes sideways.

Strengths of This Valuation Method

For a real estate syndicator, the benefits of this approach are crystal clear. It builds a valuation framework that speaks the language of investors and is squarely focused on returns.

- Investor-Centric Logic: It treats the property like what it is—a financial asset. The valuation is based entirely on its performance, which is exactly how an investor thinks.

- Data-Driven Decisions: This method forces you to get your hands dirty with the numbers. You have to dig into the property’s financial history and the local market, which helps take emotion out of the equation.

- Direct Market Comparison: Using a cap rate pulled from recent, comparable sales keeps your valuation grounded in reality. It reflects what other investors are actually paying for similar assets in the current market.

Where The Income Approach Falls Short

As powerful as it is, this method isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. It's important to recognize where it just doesn't fit, or where it can even be misleading if you feed it bad data.

The income capitalization approach is a powerful tool, but its output is only as reliable as the inputs you provide. Inaccurate income projections or a misjudged cap rate can lead to a significantly flawed valuation.

This is precisely why it’s not the go-to method for properties where rental income isn't the main point. Take a single-family home that the owner lives in, for example. There's no rental income to analyze, so an appraiser is going to rely almost exclusively on the sales comparison approach, looking at what similar homes in the neighborhood have recently sold for.

Trying to value raw land or a special-use property like a church or a school with this method would also be a struggle. Their value simply isn’t tied to a predictable stream of income.

Sure, you could try to project potential income for these properties, but your numbers would be highly speculative at best. For these non-income-producing assets, the sales comparison or cost approach usually gives you a much more reliable and defensible valuation. In fact, the smartest analysts often use multiple methods to triangulate a property's value. If all three approaches point to a similar number, you can be much more confident you're seeing the full picture.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Income Approach

As you start using the income capitalization approach, you'll naturally run into some common questions. It's a fantastic tool for any serious investor, but mastering its finer points takes a bit of practice. Let's tackle some of the most frequent queries head-on.

What Is Considered a Good Cap Rate?

This is the classic question, but the answer is always: "it depends." There's no magic number that works for every property. A "good" cap rate is entirely relative to the property type, its location, and the current market conditions.

Think of it this way: a brand-new apartment building in a hot downtown market might trade at a 4% cap rate. That sounds low, but it reflects the high demand and low perceived risk. On the other hand, you might look for a 10% cap rate on an older commercial building in a smaller town to compensate for the higher risk and less predictable future. A good cap rate is simply one that fairly balances the risk you're taking with the return you expect for that specific asset.

How Is This Different From a Sales Comparison?

The income approach and the sales comparison approach are two sides of the same valuation coin. They look at value from different angles, and when they align, you can be much more confident in your numbers.

- The Income Approach asks: "What is this property worth based on the money it makes?" It's all about the earning potential and cash flow.

- The Sales Comparison Approach asks: "What are people actually paying for similar properties nearby?" This method is grounded in recent, real-world market transactions.

Smart investors and professional appraisers never rely on just one. Using both gives you a crucial cross-check. If your income-based valuation and your sales comps point to a similar price, you're on solid ground.

Can I Use This for a Single-Family Home?

Absolutely, but with one big caveat: it has to be an investment property. If you're buying a house specifically to rent it out, you can and should run the numbers. Calculate its Net Operating Income (NOI), find a suitable cap rate for your local market, and you'll get a solid investment valuation.

However, if you're buying the home to live in yourself, the income capitalization approach doesn't apply because there's no rental income. For owner-occupied homes, appraisers will lean almost exclusively on the sales comparison approach to determine value.

One of the biggest mistakes I see people make is including their mortgage payment (debt service) in the operating expenses when calculating NOI. Another common slip-up is forgetting to account for potential vacancy. Both of these errors will make your NOI look much better than it really is, leading you to overpay for a property.

Juggling all the moving parts of a real estate syndication—from raising capital to sending out investor updates—is a massive undertaking. Homebase is an all-in-one platform built to automate those very tasks, freeing you up to do what you do best: find great deals. It gives you a central hub for deal management, investor relations, and compliance, all for a simple flat fee. See how Homebase can help you scale your business more efficiently.

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

DOMINGO VALADEZ is the co-founder at Homebase and a former product strategy manager at Google.

What To Read Next

A Guide to Real Estate Financial Modelling for Syndicators

Blog

Master real estate financial modelling with this guide. Learn to build models that analyze deals, forecast returns, and build unwavering investor confidence.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

© 2026 Homebase. All rights reserved.