What Is Qualified Nonrecourse Financing? Key Insights & Benefits

What Is Qualified Nonrecourse Financing? Key Insights & Benefits

Learn what is qualified nonrecourse financing, how it works for real estate investors, and its advantages for your tax and investment strategies.

Domingo Valadez

Aug 2, 2025

Blog

At its most basic level, qualified nonrecourse financing is a special type of loan for real estate where the lender can only seize the property itself if you default. In other words, your personal assets are completely off-limits. This structure provides a powerful shield for investors.

Understanding Qualified Nonrecourse Financing

Think of it like a standard real estate loan, but with a significant tax superpower. While most nonrecourse loans protect your personal bank account and other assets from seizure, they often fall short when it comes to deducting investment losses on your tax return.

This is where the "qualified" part becomes a game-changer.

Qualified nonrecourse financing carves out a specific exception to the IRS’s "at-risk" rules. Typically, these rules say you can only deduct losses up to the amount of money you personally stand to lose in a deal. A standard nonrecourse loan usually doesn't count toward this "at-risk" amount, which can severely limit your ability to write off losses against your income.

But when a loan meets the strict criteria to be considered qualified, the whole game changes.

The Power of "Qualified" Status

So, what exactly makes this type of financing so special? Its real power lies in how it interacts with tax laws, specifically how it lets you increase your at-risk amount for the investment.

This means you can potentially deduct losses that are greater than your initial cash investment. This is a massive advantage in real estate, where large depreciation expenses often create significant "paper" losses that can be used to offset other income.

This special status allows investors to include the borrowed amount in their tax basis for deducting losses, unlocking significant tax-saving opportunities that would otherwise be unavailable.

The U.S. tax code is very precise about what qualifies. To get this treatment, a loan must be used for the activity of holding real property and be secured exclusively by that property. You can dig into the specific legal language on the Cornell Law School website, which outlines the requirements under 26 CFR § 1.465-27.

This distinction is the key that unlocks major tax benefits, making it an incredibly valuable tool in real estate partnerships and syndications.

To help clarify, here's a quick breakdown of the core features that define this type of financing.

Key Characteristics of Qualified Nonrecourse Financing

Ultimately, these characteristics work together to create a financing structure that offers both asset protection and significant tax advantages for real estate investors.

How the At-Risk Rules Shape Your Tax Deductions

Before we can really appreciate what makes qualified nonrecourse financing so powerful, we have to talk about something called the at-risk rules. These IRS rules, officially known as Section 465 of the tax code, were put in place to stop investors from claiming huge "paper losses" on money they didn't actually stand to lose.

At its core, the rule is simple: you can only deduct investment losses up to the amount of capital you have "at risk." This includes the cash you put into the deal and any debt you are personally on the hook for. If you lose it, it comes out of your pocket.

This is precisely where standard nonrecourse financing runs into a problem. Because you aren’t personally liable for that loan, the IRS typically says it doesn't count toward your at-risk amount.

A Tale of Two Loans

Let's walk through an example to see this in action. Imagine you invest $100,000 in cash into a real estate deal. The property is bought using a $400,000 standard nonrecourse loan. In the first year, thanks to depreciation, the property generates a paper loss of $120,000.

Since that $400,000 loan is standard nonrecourse, your at-risk amount is limited to your $100,000 cash investment. That means you can only deduct $100,000 of the loss, even though the property's total loss was $120,000. The leftover $20,000 loss gets suspended, carried forward to future years where you might be able to use it—but you can't use it now.

This limitation seriously waters down one of the most attractive parts of real estate investing: the tax shield from depreciation. It highlights why it's so critical to understand all the real estate investment tax benefits at your disposal.

Key Takeaway: With standard nonrecourse debt, your deductible losses are capped by your personal cash in the game, not the full investment size.

How Qualified Nonrecourse Financing Flips the Script

Now, let's see what happens when that same loan meets the strict IRS criteria to become qualified nonrecourse financing. This is where everything changes. The IRS created a special carve-out, allowing this specific type of debt to be included in your at-risk basis.

Let's rewind our example, but this time with the right kind of financing:

- Cash Investment:$100,000

- Qualified Nonrecourse Loan:$400,000

- Total At-Risk Amount:$500,000 ($100,000 cash + $400,000 loan)

The property still generates that same $120,000 paper loss. But your ability to use it is completely different. Because your at-risk basis is now a whopping $500,000, you can deduct the entire$120,000 loss on this year's tax return. Nothing gets suspended.

This single change unlocks the full tax-saving potential of a real estate investment. For partners in a syndication, it means they can deduct losses well beyond their cash contribution, up to their share of the qualified loan. Frankly, it's a game-changer for structuring deals to be as tax-efficient as possible.

Meeting the Criteria for Qualified Financing

For a loan to unlock the powerful tax benefits we've been talking about, it can't just be any old nonrecourse debt. It has to meet a very specific, strict set of IRS requirements to earn the label "qualified."

Think of it like a legal checklist. If you fail to tick even a single box, the loan won't count toward your at-risk basis, and those valuable tax deductions simply vanish. The IRS put these rules in place to make sure the loan is a legitimate, arm's-length financial deal—not just a clever way to cook up artificial tax losses.

So, let's break down exactly what every deal must have to pass the test.

The Core Requirements Checklist

To be considered qualified nonrecourse financing, a loan has to satisfy several conditions laid out in IRC Section 465(b)(6)(B). These aren't suggestions; they are hard and fast rules.

- It Must Be Secured by Real Property: The loan has to be borrowed specifically for the purpose of holding real estate. Critically, that same property must be the only thing securing the debt. You can’t get a loan against your stock portfolio to buy an apartment building and expect it to qualify.

- No One Can Be Personally Liable: This is the bedrock of any nonrecourse debt. Not a single partner or anyone related to them can personally guarantee repayment. The moment they do, the IRS considers it recourse debt, at least for the partner who signed the guarantee.

- The Loan Must Come from a "Qualified Person": You can't just borrow from anyone. The lender must be a qualified person, which almost always means a bank, a credit union, or a government agency. This rule is there to prevent borrowing from people who might have a vested, and potentially manipulative, interest in the deal's tax outcome.

- The Lender Cannot Be a Related Party: This is a big one. You generally can't get your financing from the person who sold you the property or from a relative. It’s a crucial anti-abuse rule designed to ensure the loan terms are standard market rates, not something cooked up to create a tax advantage.

- It Cannot Be Convertible Debt: The loan agreement can't include a feature that lets the lender convert the debt into an ownership stake (equity) in the property. The lender’s role is to be a lender, not to become a partner down the road.

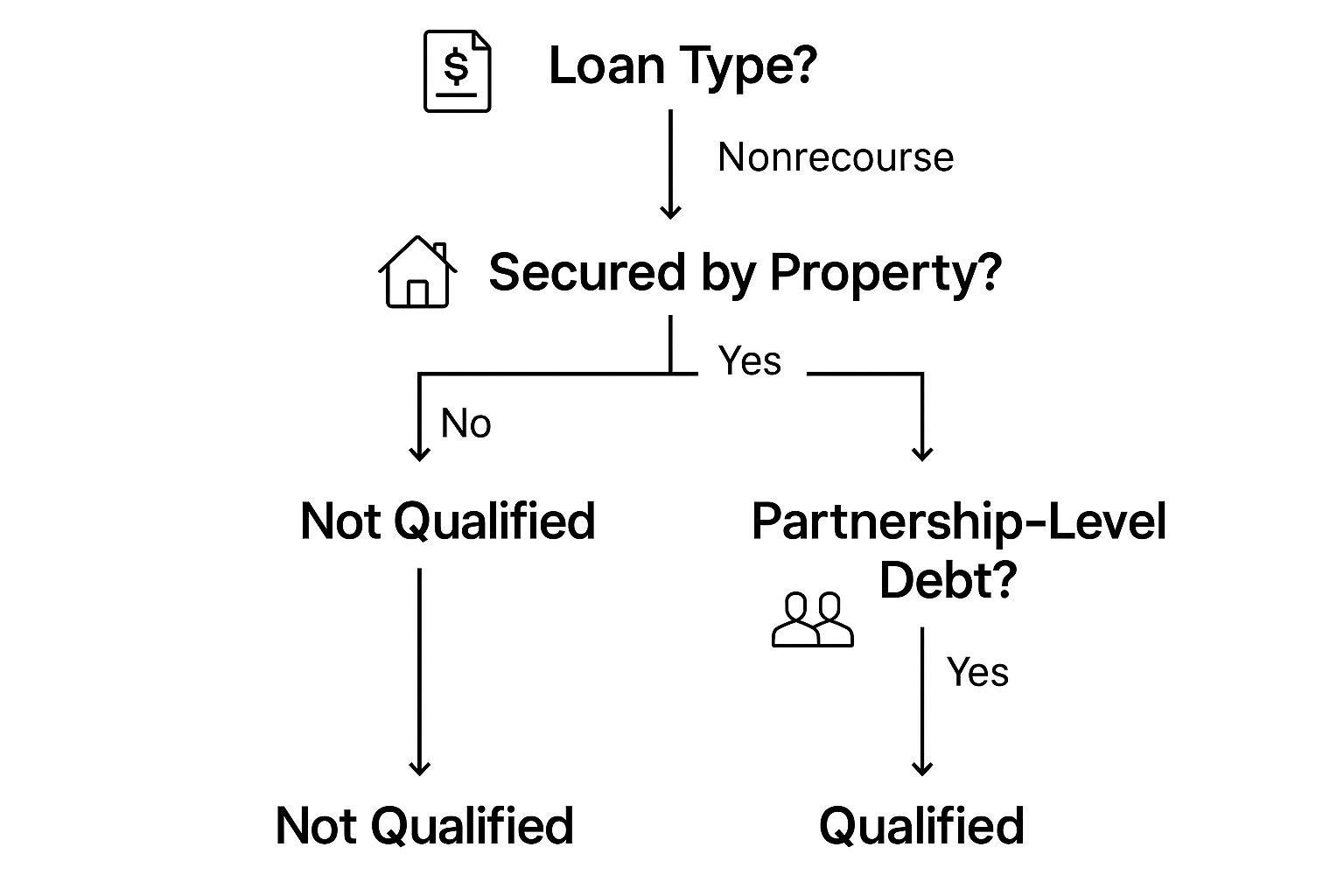

This decision tree gives you a clear visual for how a loan must navigate these standards.

As you can see, a "no" at any point in the process immediately knocks the loan out of the running for this special tax treatment.

Putting It All Together in a Real-World Scenario

Let's walk through an example. Imagine an investment group, "Apex Syndications," wants to acquire a $5 million apartment complex. They need $3.5 million in financing to close the deal. To make sure their investors get the best possible tax advantages, they have to structure this loan perfectly.

The source of the loan is just as important as its structure. A loan from the property seller, even if it's nonrecourse, will almost always fail to qualify.

First, Apex borrows from a national commercial bank—a clear-cut qualified person. Second, the loan is secured only by the apartment complex itself, with no other business or personal assets pledged as collateral. Third, none of the general partners or their spouses personally guarantee the debt. And finally, the loan is a straightforward debt instrument; there are no hidden clauses allowing the bank to convert its debt into an ownership position.

By meticulously checking every box, Apex ensures their $3.5 million loan is genuine qualified nonrecourse financing. This is what allows their passive investors to add their pro-rata share of that debt to their at-risk basis, unlocking the full potential for tax deductions right from the start.

Unlocking Value in Real Estate Partnerships

While the asset protection and at-risk rules are a big deal, qualified nonrecourse financing truly shines in the world of real estate partnerships and syndications. For groups of investors who pool their money, this type of loan is often the engine that makes a deal not just possible, but incredibly appealing from a tax perspective.

Here’s why it's so important: it allows passive investors to significantly increase their tax basis in the partnership. This is the key that unlocks their ability to deduct a share of the property's losses—most notably depreciation—even when those losses are way more than the cash they initially put in. Without it, those valuable tax benefits would be stuck behind a much lower ceiling.

The Basis Boost in Action

To really grasp how powerful this is, let's walk through a concrete example.

Picture a group of investors forming a partnership to buy an apartment building for $10 million. The investors contribute a total of $3 million in cash, and the partnership gets a $7 million qualified nonrecourse loan from a commercial bank to cover the rest.

Now, let's say in the first year, the property generates a large "paper loss" of $500,000, mostly from depreciation. How does this affect a passive partner who invested $150,000 for a 5% stake?

- Their Share of the Loss: Their slice of that $500,000 loss is $25,000 (5%).

- Their Initial At-Risk Basis (Cash Only): At first glance, their at-risk basis is just the $150,000 cash they invested.

- Their Share of the Loan:This is the magic. They also get to add their 5% share of the $7 million loan to their basis, which comes out to $350,000.

- Their Total At-Risk Basis:$500,000 ($150,000 cash + $350,000 from the loan).

Because their total at-risk basis of $500,000 is much greater than their $25,000 share of the loss, they can deduct the full amount on their personal tax return. If this wasn't a qualified loan, they'd be capped by their cash investment, and a huge chunk of that tax benefit would be lost, at least for the time being.

This is a bedrock concept in partnership taxation. The tax code, specifically IRC Section 465, treats partners as if they bear the economic risk for this specific type of debt, allowing it to increase their basis. That's what permits them to claim these all-important losses. For a deeper dive into the mechanics, you can explore detailed insights on nonrecourse deductions from The Tax Adviser.

For syndicators, being able to clearly explain this benefit is how you attract savvy passive investors. The power to generate tax losses that are bigger than an investor's cash contribution is one of the most compelling advantages of investing in large-scale real estate.

Ultimately, qualified nonrecourse financing is a cornerstone of modern real estate investment. It’s what allows deal sponsors to structure projects that are not only profitable on paper but also remarkably tax-efficient in practice. This creates a true win-win for both the deal sponsors and their limited partners.

Weighing the Pros and Cons for Your Investment

Qualified nonrecourse financing can be a powerful tool, especially for the tax advantages it offers, but it's certainly not a one-size-fits-all solution. Think of it less as a standard loan and more as a specialized financial instrument. Before you jump into a deal using this structure, you have to look at the whole picture—the good, the bad, and the practical trade-offs.

The upsides are what draw sophisticated investors in. The biggest advantage, by far, is how it supercharges your tax deductions. By including the loan amount in your at-risk basis, you can deduct paper losses from things like depreciation that often dwarf your actual cash contribution. It's a game-changer for your tax return.

On top of that, you get a serious layer of personal asset protection. If the investment unexpectedly fails, the lender can only go after the property itself. Your home, personal savings, and other investments are off-limits. This protection gives investors the confidence to pursue larger properties without putting their entire net worth on the line.

Balancing the Benefits with the Drawbacks

Of course, these powerful benefits don’t come without a cost. Lenders are shouldering a lot more risk when they can't come after your personal assets, and they build that risk right into the loan's terms. You have to be ready for a tougher set of conditions than you'd find with a standard recourse loan.

The core trade-off is simple: investors gain powerful tax benefits and asset protection, while lenders compensate for their increased risk by charging more and demanding better deal fundamentals.

So, how do lenders protect themselves? They typically tighten the screws in a few key areas:

- Higher Interest Rates: Don't be surprised to see a higher interest rate. This premium is the lender's direct compensation for taking on extra risk, and you absolutely must bake this higher cost into your financial models to make sure the deal still pencils out.

- Larger Down Payments: Lenders want to see you have more skin in the game. It’s common to see down payment requirements of 30% or more, which is a significant jump from the 20% you might see on a traditional loan.

- Stricter Underwriting: The property itself goes under a microscope. Lenders need to be confident that the asset is top-tier with a history of strong, reliable cash flow. Since the property is their only way to get their money back, they'll analyze it far more intensely.

On top of the stricter terms, just finding a loan that meets the legal definition of what is qualified nonrecourse financing can be a challenge. The rules about using a qualified lender and steering clear of related-party transactions add complexity to the process.

In the end, it boils down to a critical decision: are the incredible tax shield and asset protection worth navigating the tougher, more expensive loan terms for your specific deal?

Beyond Real Estate: A Look at Other Applications

While qualified nonrecourse financing is practically synonymous with real estate, its core principles have popped up in other areas, most notably the renewable energy sector. It turns out the government loves using these kinds of financial structures as a lever to encourage investment in high-priority industries, and clean energy is squarely on that list.

Picture an investor putting money into a large-scale solar farm. One of the biggest carrots for that investor is the Investment Tax Credit (ITC), which offers a sweet dollar-for-dollar reduction in their income tax bill. But here’s the catch: just like in real estate, the size of that credit hinges on the investor's "at-risk" amount.

Protecting Tax Credits in Renewable Energy

This is where the idea of "qualified" financing becomes absolutely essential. If the solar project gets funded with regular, run-of-the-mill nonrecourse debt, the investor's tax credit basis can get hammered. The IRS sees that loan as money the investor isn't truly risking, which shrinks the very tax benefit that was meant to attract them in the first place.

But when the project uses financing that follows the same playbook as qualified nonrecourse financing, the story has a much happier ending. This structure allows the entire loan amount to be included in the basis for calculating that valuable tax credit.

The way a loan is structured can make or break the value of tax incentives. For investors to get the full financial benefit of backing renewable energy, using the right kind of nonrecourse financing is non-negotiable.

When we're talking about U.S. energy tax credits, this distinction is a big deal for figuring out the eligible basis for those ITCs. If the financing doesn't meet the specific "qualified" standards, it can actually lower the property's credit basis, which in turn shrinks the tax benefits investors were counting on.

To keep that credit intact, the financing usually has to meet a few key tests:

* It must come from an unrelated qualified lender.

* It cannot exceed 80% of the project's credit base.

This shows just how adaptable these rules are, tailored to fit the unique needs of different industries. You can dive deeper into why being "at-risk" is a good thing for tax purposes on leoberwick.com.

Seeing this parallel in another sector really highlights how flexible and important this financial tool is. It's a go-to strategy for the government to guide private capital toward areas it considers critical for the country's future, whether that's building homes or developing sustainable energy.

Diving Deeper: Your Top Questions Answered

When you get into the nitty-gritty of a deal, especially one involving complex financing, questions are bound to pop up. Let's tackle some of the most common ones that investors have about qualified nonrecourse financing. Getting these details right is crucial for making smart moves in real estate syndication.

Can the Seller of the Property Provide the Loan?

This is a frequent point of confusion, and the answer is a firm no. The IRS is very specific here. To be considered "qualified," the financing must come from a "qualified person"—think traditional banks, credit unions, or other institutional lenders.

Sellers, deal sponsors, or anyone related to them are explicitly excluded. This rule exists to prevent potential conflicts of interest and ensure the loan terms are at arm's length.

What if a Partner Personally Guarantees the Debt?

This is where things can get tricky. If even one partner personally guarantees a piece of the loan, that portion of the debt instantly changes character for that specific partner. It becomes recourse debt in their eyes.

As a result, they can no longer include that guaranteed amount in their at-risk basis, which effectively shrinks the tax benefits they were hoping to gain. The rest of the non-guaranteed loan can still be qualified for the other partners, but the guarantee carves out an exception for the individual who signed on the dotted line.

Can Any Property Be Used as Collateral?

Not just any asset will do. For a loan to be "qualified," the IRS requires it to be secured solely by real property—the land and buildings involved in the investment.

You can't pledge personal assets like your stock portfolio or another business you own as collateral. The financing has to be tied directly to the real estate itself, making it the one and only thing the lender can seize if the deal goes south.

Why Are the Interest Rates Often Higher?

This is the classic risk-reward trade-off. Lenders aren't just being difficult; they're protecting themselves.

Because the lender’s only remedy in a default is to foreclose on the property, they take on significantly more risk. To compensate for this, lenders typically charge higher interest rates and may require larger down payments, often 30% or more.

Ultimately, you're paying a premium for the incredible benefit of shielding your personal assets and gaining a powerful tax advantage. It’s a cost of doing business that most seasoned investors find well worth the price.

Ready to streamline your real estate syndication and impress your investors? Homebase provides an all-in-one platform to manage fundraising, investor relations, and deal administration effortlessly. Stop juggling spreadsheets and start focusing on growth. Learn more at https://www.homebasecre.com/.

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

DOMINGO VALADEZ is the co-founder at Homebase and a former product strategy manager at Google.

What To Read Next

A Guide to Real Estate Financial Modelling for Syndicators

Blog

Master real estate financial modelling with this guide. Learn to build models that analyze deals, forecast returns, and build unwavering investor confidence.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

© 2026 Homebase. All rights reserved.