Cost Approach Real Estate Explained for Syndicators

Cost Approach Real Estate Explained for Syndicators

Master the cost approach real estate valuation method. Learn how to calculate value, avoid common pitfalls, and leverage it for your next syndication deal.

Domingo Valadez

Jan 26, 2026

Blog

The cost approach in real estate is a valuation method that essentially asks one simple question: What would it cost to rebuild this exact property from the ground up, right now?

This whole idea is built on the principle of substitution. Think about it—a savvy buyer isn't going to pay more for an existing building than it would cost them to buy the land and construct a brand-new, equivalent one.

Understanding The Core Logic Of The Cost Approach

Here's an easy way to picture it. Imagine you have two choices: buy a five-year-old car or build the exact same model from scratch with brand-new parts. The cost approach works the same way for property. You start with the price tag of the "new replica" and then subtract value for the age, wear, and tear of the existing building.

What’s great about this method is how tangible it is. It strips away market speculation and income projections, focusing instead on the physical nuts and bolts of the structure and the dirt it sits on.

The Fundamental Formula

At its core, the cost approach formula is beautifully simple. It gives you a clear, logical path to value a property based on its physical components.

The entire calculation comes down to one equation:

(Replacement Cost - Accumulated Depreciation) + Land Value = Property Value

Each part of this formula is doing a specific job. You’re calculating the cost to build new, accounting for the value lost over time, and then adding in the separate value of the land itself. It's a comprehensive physical assessment.

Why It Matters For Syndicators

For a real estate syndicator, this isn't just theory—it's a crucial part of smart underwriting. While you’ll almost always lean on income or sales comps, the cost approach acts as a powerful reality check. To get a complete picture, it's always wise to explore multiple professional techniques, including Mastering Real Estate Property Valuation Methods.

This approach becomes particularly indispensable in a few key situations:

- New Developments: When you're building something new, there's no sales history or income stream to analyze. The cost approach is often your primary tool for establishing value.

- Unique Assets: How do you find comps for a school, a data center, or a specialized industrial plant? You probably can't. The cost approach becomes essential for these special-use properties.

- Volatile Markets: In a hot market where comps might be inflated by bidding wars, the cost approach provides a conservative, defensible floor for your valuation.

Understanding all three commercial property valuation methods is non-negotiable for serious investors. But the cost approach gives you a unique backstop, grounding your analysis in hard costs and preventing you from overpaying based on market hype.

Breaking Down The Cost Approach Formula

On the surface, the cost approach formula seems straightforward. But its real power is buried in the details of each component.

Don't think of it as a rigid mathematical equation. It’s more like a structured investigation into what a property is physically worth. For a syndicator, getting comfortable with these pieces turns the formula from appraisal jargon into a powerful tool for analyzing deals.

The core formula is: (Replacement Cost - Accumulated Depreciation) + Land Value = Property Value.

Let's unpack each element one by one to see how they fit together.

Component One: Replacement Cost

First, you have to figure out the replacement cost. This isn't about what it would cost to build an exact replica of the existing, and possibly outdated, building. Instead, it’s the estimated expense to construct a brand-new building with the same utility—size, number of units, function—but using today's materials, standards, and design.

Picture a 1970s apartment building. It probably has shag carpets, popcorn ceilings, and an inefficient layout. You wouldn't rebuild it with those exact features today. The replacement cost would be the price to build a modern apartment complex with the same square footage and unit count, just with current construction methods and finishes. That’s the core of replacement cost.

You might also hear the term reproduction cost, which means building an exact duplicate of the property, flaws and all. This is rarely used unless you're dealing with historic buildings where replicating the original craftsmanship is the whole point. For pretty much all real estate syndication, replacement cost is what matters.

So, where does this number come from? Appraisers don't just pull it out of thin air. They have a few go-to methods:

- Cost Manuals: Resources like the Marshall & Swift Valuation Service are industry bibles, providing detailed, up-to-date construction cost data per square foot for all kinds of buildings in different regions.

- Local Builder Consultations: A good appraiser will often just pick up the phone and talk to local contractors. This gives them a real-world gut check on current labor and material prices in that specific market.

- Cost-Segregation Services: These specialized firms can provide an incredibly detailed breakdown of a building’s components, which helps create a very precise cost estimate.

A solid grasp of construction expenses, like those in a guide to building duplexes cost, is essential for getting this part right. This first step effectively sets the baseline value—the price of a brand-new, comparable substitute property.

Component Two: Accumulated Depreciation

Okay, you have the cost to build a new version of the property. But the property you're analyzing isn't new. This is where depreciation comes in. It's the quantifiable loss in value from that shiny, new replacement cost.

In the world of appraisals, depreciation is much more than simple wear and tear.

Key Insight: Depreciation here is an economic concept—a real loss in market value. It's not the same thing as the accounting term you use on your tax returns. It's broken down into three distinct categories every investor needs to understand.

Each type of depreciation chips away at the replacement cost for a different reason.

The Three Types of Depreciation

- Physical Deterioration: This is the one everyone thinks of. It’s the tangible decay of the property from age and use—a leaky roof, a cracked foundation, an old HVAC system, or peeling paint. It’s the value lost simply because the building is older and more worn out than a new one.

- Functional Obsolescence: This is about a loss in value because of an outdated design or features that just don't meet modern expectations. For a multifamily property, this could be tiny closets, a choppy floor plan instead of an open concept, or a lack of in-unit laundry. The property is less desirable because its function is out of style.

- External Obsolescence: This is a loss in value caused by factors completely outside the property lines, things the owner has zero control over. Maybe a noisy factory was built next door, the city changed zoning laws for the worse, or a major local employer packed up and left town, hurting the rental market.

Pinpointing the exact dollar amount for these three types of depreciation is easily the most subjective and challenging part of the cost approach. It’s where a great appraiser's deep market knowledge really earns its keep.

Component Three: Land Value

The final piece of the puzzle is the land value. The cost approach smartly treats the land and the building as two separate things. Why? Because buildings wear out and depreciate over time, but land typically doesn't—in fact, it often appreciates.

To figure out the land's value, an appraiser asks a simple question: "What would a vacant lot of this size, in this location, and with this zoning sell for on the open market today?"

They answer this by looking at recent sales of similar, undeveloped land parcels in the immediate area. This value is then added back to the depreciated cost of the building.

Separating the two just makes sense. You could have two identical apartment buildings, but if one is sitting on a prime downtown corner and the other is in a remote suburb, their total values will be worlds apart. That huge difference is captured almost entirely by the land value.

When you bring all three elements together, you get a clear, asset-based valuation that’s grounded in what it would physically cost to replace the property today.

A Practical Cost Approach Walkthrough For A Multifamily Asset

Abstract formulas are great, but the real "aha!" moment comes when you apply valuation theory to an actual deal. Let's get our hands dirty and walk through a step-by-step cost approach valuation for a hypothetical 100-unit multifamily development project.

By putting real numbers to the process, we can see exactly how a syndicator or appraiser would build this valuation from the ground up. This example will serve as our blueprint, showing how each piece of the formula fits together to arrive at a final, defensible value.

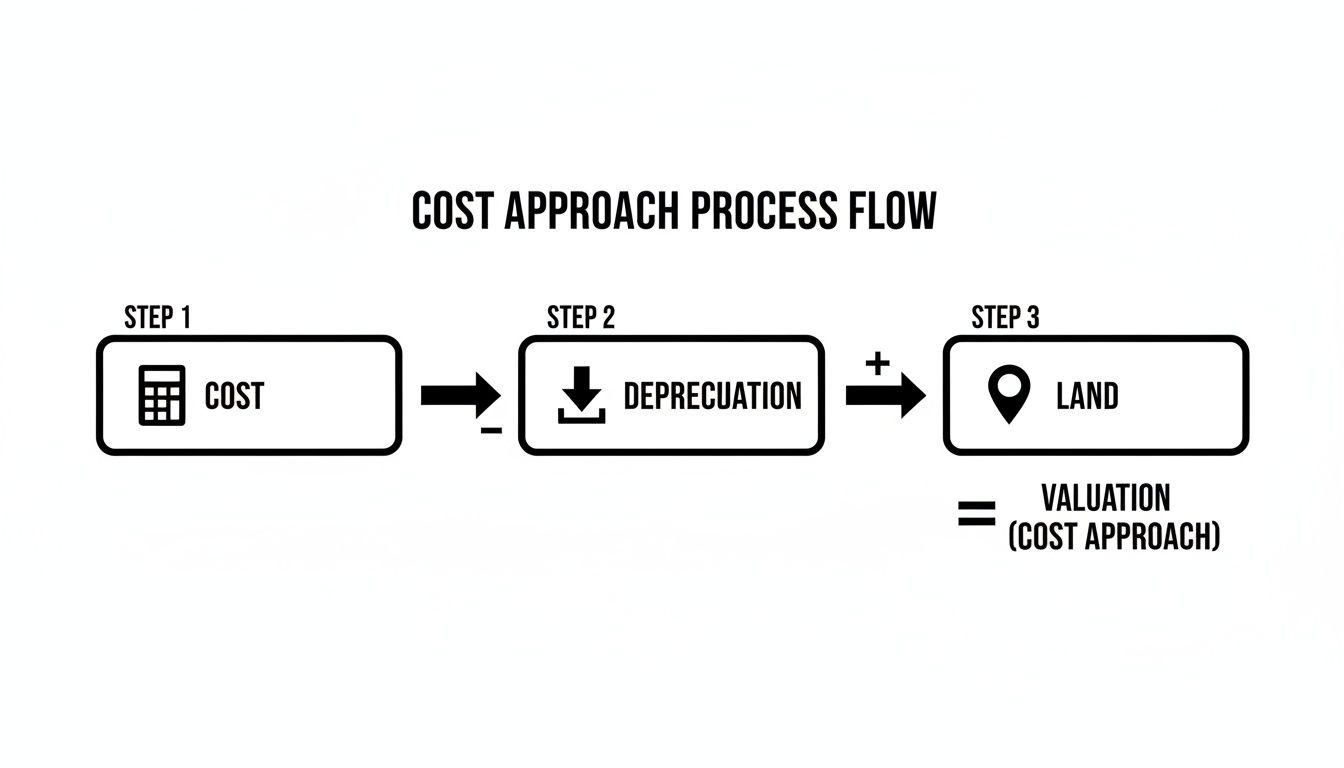

The flowchart below breaks down the simple, three-part logic we'll be following.

As you can see, the core of this method is really just a simple addition and subtraction exercise, all anchored by the principle of substitution.

Step 1: Calculate The Replacement Cost New

Our hypothetical property is a planned 100-unit apartment complex. The total proposed gross building area comes out to 125,000 square feet.

To figure out the Replacement Cost New (RCN), we need a reliable, current cost-per-square-foot to build a similar multifamily property in this specific market. After talking to a few local GCs and cross-referencing a trusted cost guide like the Marshall & Swift Valuation Service, we land on an all-in construction cost of $200 per square foot.

The math from here is pretty simple:

- 125,000 sq. ft. x $200/sq. ft. = $25,000,000

This $25 million figure represents what it would cost to build a brand-new, modern equivalent of our property from scratch today. It’s the starting point for our entire valuation—the property’s value in perfect, new condition.

Step 2: Quantify All Forms Of Depreciation

Next, we have to account for any loss in value. Even though we’re modeling a new development, let’s imagine the building is just one year old for this example. It's the perfect way to see how depreciation actually gets calculated in the real world.

Depreciation isn't just one number; it’s the sum of three very different kinds of value loss.

- Physical Deterioration: Let's say construction was delayed, and the building frame was exposed to the elements longer than planned. This caused some minor, premature wear. We're talking about needing to repaint some exterior surfaces and replace a few weathered fixtures. An appraiser might estimate this "curable" physical issue at $150,000.

- Functional Obsolescence: The original floor plans called for a lot of studio apartments. But a fresh market study shows that the real demand is for two-bedroom units. This inefficient unit mix makes our property less attractive than a competitor with an ideal layout. That's a classic example of functional obsolescence, and the appraiser quantifies this loss of utility at $500,000.

- External Obsolescence: Here's a curveball. Six months after we broke ground, the city rezoned an adjacent lot to allow for a new industrial facility. The future noise and truck traffic will definitely hurt the appeal of our apartments. This is an external factor completely beyond our control, and the appraiser estimates the value lost due to this "economic" obsolescence is $850,000.

Now, we just add them all up to get our total depreciation.

Total Depreciation = $150,000 (Physical) + $500,000 (Functional) + $850,000 (External) = $1,500,000

This $1.5 million represents the total value that has been chipped away from our starting point, the "perfect condition" replacement cost.

Step 3: Determine The Land Value

Remember, the building and the land are two separate things. The land itself doesn't depreciate; its value is simply what a similar vacant parcel would sell for on the open market today.

To pin this down, an appraiser would dig into recent sales of comparable, commercially-zoned lots right in our neighborhood. Based on that research, the market value for our property's five-acre parcel is determined to be $4,000,000.

Step 4: Arrive At The Final Property Value

We have all three pieces of the puzzle. Now we can plug them into the cost approach formula and bring it home.

- Start with Replacement Cost New: $25,000,000

- Subtract Total Accumulated Depreciation: - $1,500,000

- Add the Land Value: + $4,000,000

This brings us to our final indicated property value.

($25,000,000 - $1,500,000) + $4,000,000 = $27,500,000

So, based on this detailed analysis, the estimated value of our 100-unit multifamily asset is $27,500,000. This hands-on example gives you a clear model for how to apply this method and ground your underwriting in tangible, asset-based numbers.

When Does The Cost Approach Actually Make Sense For Syndicators?

For any real estate syndicator, knowing how to run the numbers for the cost approach is one thing. The real skill is knowing when to use it. This method isn't your go-to for every deal, but in the right situation, it can be the most important reality check you have.

Think of it as your underwriting backstop. While the income approach focuses on cash flow and the sales approach looks at what others are paying, the cost approach grounds your analysis in physical reality. It answers one simple, powerful question: could someone just build this same thing today for less than we're about to pay?

New Construction and Development Deals

This is the most straightforward application. When you’re looking at a ground-up development deal, there’s no income stream to analyze yet. And you can't find direct sales comps for a building that doesn't even exist.

In this case, the cost approach isn’t just an option; it's the foundation of your entire pro forma. It’s how you:

- Build the Budget: The total cost to build—from labor and materials (hard costs) to architectural plans and permits (soft costs)—is the "Replacement Cost" in your valuation formula.

- Estimate Stabilized Value: The final number you get from the cost approach serves as the initial benchmark for what the finished, stabilized property will be worth before it has any operating history.

For any new build, the cost approach is where your valuation begins and ends.

Valuing Unique and Special-Use Properties

What’s the market cap rate for a courthouse? How do you pull sales comps for a custom-built cold storage facility or a church? For these kinds of special-use properties, the other valuation methods just don't work.

Assets like schools, government buildings, or highly specialized industrial plants don't trade on the open market often, and they don't generate conventional rental income. Here, the cost approach becomes the only logical way to pin down a value. It focuses purely on what it would cost to build a functional equivalent from scratch.

The Ultimate Sanity Check in Frothy Markets

This is arguably the most critical use for the cost approach in syndication. When a market gets hot, it’s easy to get swept up in the momentum. Cap rates get squeezed, bidding wars inflate sales prices, and before you know it, you could be massively overpaying.

Key Insight: The cost approach anchors your valuation in the real world. If the price you're justifying with income or sales comps is way higher than what it would cost to build a brand-new competitor next door, that's a huge red flag.

This simple comparison can save you from making a classic mistake: paying more for a dated, 20-year-old apartment building than it would cost to construct a shiny new one down the street. It acts as a conservative guardrail, protecting you and your investors from irrational exuberance and building confidence that you've stress-tested the deal.

To help you decide which valuation method to lean on for your next deal, it's useful to see them side-by-side. Each one has its place, and the best underwriters know how to triangulate the truth by using all three.

The table below breaks down the ideal scenarios for each approach, giving you a quick reference for your analysis.

Valuation Method Use Cases For Real Estate Syndicators

Ultimately, no single method tells the whole story. By using the cost approach as a rational backstop to the market-driven and income-driven valuations, you get a much clearer, more defensible picture of a property's true worth.

Common Pitfalls and Limitations to Avoid

The cost approach gives you a fantastic, asset-based reality check for your underwriting, but like any tool, it has its limits. If you want to use it well and confidently defend your analysis to investors, you have to know its weak spots and where the numbers can steer you wrong. Overlooking these limitations can lead to some seriously flawed assumptions and risky deals.

The single biggest headache with the cost approach is trying to accurately estimate accumulated depreciation. It’s much more of an art than a science. Sure, you can calculate physical wear and tear with some confidence (like the cost to replace a 20-year-old roof), but functional and external obsolescence are a whole different beast.

How do you put a precise dollar value on a funky, outdated floor plan? Or calculate the financial hit from a new factory opening up next door? That requires deep market knowledge, and even then, two experienced appraisers could come up with wildly different numbers. This subjectivity is the method’s Achilles' heel.

Navigating Volatile Construction Costs

Another major challenge is pinning down the "Replacement Cost New" (RCN) when the market is all over the place. Construction costs aren't static; labor and materials can swing dramatically based on supply chain issues, inflation, or even a local building boom that creates a labor shortage. A cost estimate you got six months ago could be totally useless today.

This kind of volatility makes the cost approach a less reliable anchor in unstable construction markets. If you don't have current, localized cost data, your entire valuation is built on a foundation of sand.

Key Takeaway: The cost approach is just a snapshot in time. Its accuracy is highly dependent on stable markets for both construction and land, and that’s never a guarantee.

This is exactly why you can’t just pull generic national averages for the cost approach in real estate. You have to talk to local builders or use up-to-the-minute cost estimation services, otherwise you risk being way off the mark.

The Problem with Older Properties

The cost approach really starts to lose its punch the older a property gets. Think about it: trying to calculate 50 years of depreciation for an old building across all three categories—physical, functional, and external—is an exercise in speculation. It’s incredibly complex.

With older assets, the depreciation figure gets so large that it can easily overshadow every other part of the formula. A small percentage error in a massive depreciation estimate can throw your final value off by a huge margin, making the result feel less than credible. For mature, income-generating properties, the income approach is almost always going to give you a more realistic and relevant valuation.

To sidestep these risks and use the cost approach smartly, stick to these best practices:

- Triangulate Your Value: Never, ever rely on the cost approach alone. Think of it as one leg of a three-legged stool, alongside the sales comparison and income approaches. You need all three for a stable, comprehensive valuation.

- Consult The Experts: Don’t guess. Whenever possible, get a quote from a local general contractor or a professional cost estimator to back up your replacement cost numbers.

- Acknowledge Subjectivity: Be upfront with your investors. When you present your analysis, explain that the depreciation estimates are subjective. Frame the cost approach value as a conservative, "bricks-and-mortar" floor, not the final word on market price.

By keeping these common pitfalls in mind, you can use the cost approach for what it does best—grounding your deal analysis in physical, real-world value.

Frequently Asked Questions About The Cost Approach

As you start getting deeper into real estate valuation, you'll find the cost approach is one of those methods that seems simple on the surface but has some tricky nuances. It’s a common source of questions for both new and experienced syndicators.

Let's break down some of the most common ones to give you a better feel for how it works in the real world.

How Does The Cost Approach Differ From The Sales Comparison Approach?

Think of it this way: the cost approach is like figuring out the price of a brand-new, custom-built car. You'd add up the cost of the engine, the chassis, the electronics, the labor to put it all together—every single component. It's built from the ground up.

The sales comparison approach, on the other hand, is like pricing that same car by looking at what similar used models are selling for at local dealerships. It's based entirely on what the market is paying right now for comparable assets.

One method builds value from the inside out, while the other derives it from the outside in.

- Cost Approach: This method is all about the physical components—construction costs, depreciation, and land value. It’s your go-to for unique properties like a church, a brand-new building, or any property where there just aren't good "comps" available.

- Sales Comparison Approach: This method relies completely on market transactions. It’s the gold standard for standard properties like single-family homes or condos in an active area where you can easily find plenty of recent, similar sales.

The real difference is their starting point. The cost approach starts with a hammer and nails; the sales comparison approach starts with recent sale contracts.

Is The Cost Approach Useful For Value-Add Multifamily Deals?

Absolutely, but its role isn't to be the star of the show. For a value-add multifamily deal, your valuation is almost always going to be driven by the income approach. After all, you’re buying the property for its future cash flow after you’ve improved it.

So, where does the cost approach fit in? Think of it as your reality check. It's a critical tool for managing risk and making sure your budget makes sense. It helps in two key ways:

- It Validates Your Renovation Budget: Your plan to fix the leaky roofs, outdated kitchens, and inefficient layouts is literally a "cost to cure" physical and functional depreciation. The cost approach gives you a structured way to think about and estimate those numbers.

- It Sets a Value Ceiling: This is the big one. The cost approach acts as a guardrail. If your total investment (purchase price + renovation costs) is more than what it would cost to build a similar property brand-new today, you’ve got a problem. You might be overpaying or planning to over-improve the asset for its market.

A savvy syndicator uses the cost approach to answer a crucial question: "Does it make more sense to buy and fix this, or just build new?" If building new is cheaper, you need to seriously question the deal.

While the income approach tells you about the opportunity, the cost approach keeps your feet planted firmly on the ground.

How Do I Explain A Cost Approach Valuation To Investors?

When you’re talking to potential investors, position the cost approach as your conservative, "bricks-and-mortar" valuation. It's the number that’s least affected by rosy projections or market hype.

Explain that this figure represents the tangible, physical worth of the asset if you had to rebuild it today. For many investors, this is incredibly reassuring because it's based on hard costs, not abstract ideas like cap rate compression or future rent growth.

The key is to present it alongside the other two valuation methods. Showing that you’ve analyzed the deal using the income, sales, and cost approaches demonstrates a level of thoroughness that builds incredible confidence. It proves you've stress-tested your assumptions from every angle. This kind of comprehensive analysis looks professional and instills trust when presented in your investor portal or deal room.

Can I Perform A Reliable Cost Approach Analysis Myself?

For an initial sniff test? Yes, and you absolutely should. Running a quick "back-of-the-napkin" cost approach is a fundamental skill that helps you weed out bad deals quickly before you sink time and money into them.

However, for anything formal—like a report for your lender or your final investor package—you need a licensed, third-party appraiser. No exceptions.

Professionals have access to proprietary cost databases and, more importantly, the experience to make the tough judgment calls. Accurately calculating depreciation, especially for things like functional or external obsolescence, is more of an art than a science. An appraiser's impartial assessment carries weight that your own analysis never will.

Think of it this way: your initial analysis is for your internal strategy. The appraiser's report is for external credibility.

Ready to elevate your syndication process? Homebase provides an all-in-one platform to manage fundraising, investor relations, and deals with ease. From professional deal rooms to streamlined distributions, we help you focus on what matters—closing capital and building relationships. Discover how Homebase can transform your operations.

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

Share On Linkedin

Share On Twitter

DOMINGO VALADEZ is the co-founder at Homebase and a former product strategy manager at Google.

What To Read Next

Software for Leasing Your Ultimate Syndication Guide

Blog

Discover the best software for leasing capital. This guide explains how real estate syndication tools streamline investor management and boost your ROI.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

Sign up for the newsletter

If you want relevant updates from our team at Homebase, sign up! Your email is never shared.

© 2026 Homebase. All rights reserved.